Jan 16, 2024

Blood and Gore

by Jason Stoffer

Over the holidays, I was gifted a wonderful reminder of the realities of living with a spinal cord injury. With it came the anxiety and the shortness of breath that accompanies the realization that I am a prisoner to this condition. There is no escape and there is (currently) no cure. I was also reminded that, although it is imperative that I pursue a fulfilling life with what remains, no change will be made if I don't embrace and voice my utter dissatisfaction with the progress of cure research.

Trigger warning: blood and gore ahead.

I am a paraplegic at L1. I cannot void my bladder on my own and I rely on intermittent catheterization to get the job done. The other day, while driving with my friend, Karl, my bladder became really full (I still have bladder sensation). When I tried to cath myself, I felt an obstruction. I panicked a little - this was an emergency. I don’t live in a city with a hospital, nor am I near an Urgent Care facility. I had to make it happen. I pushed a little harder and my catheter filled with blood. There was blood on my pants and now, on Karl’s floorboard. Despite the blood, I kept trying until I had success.

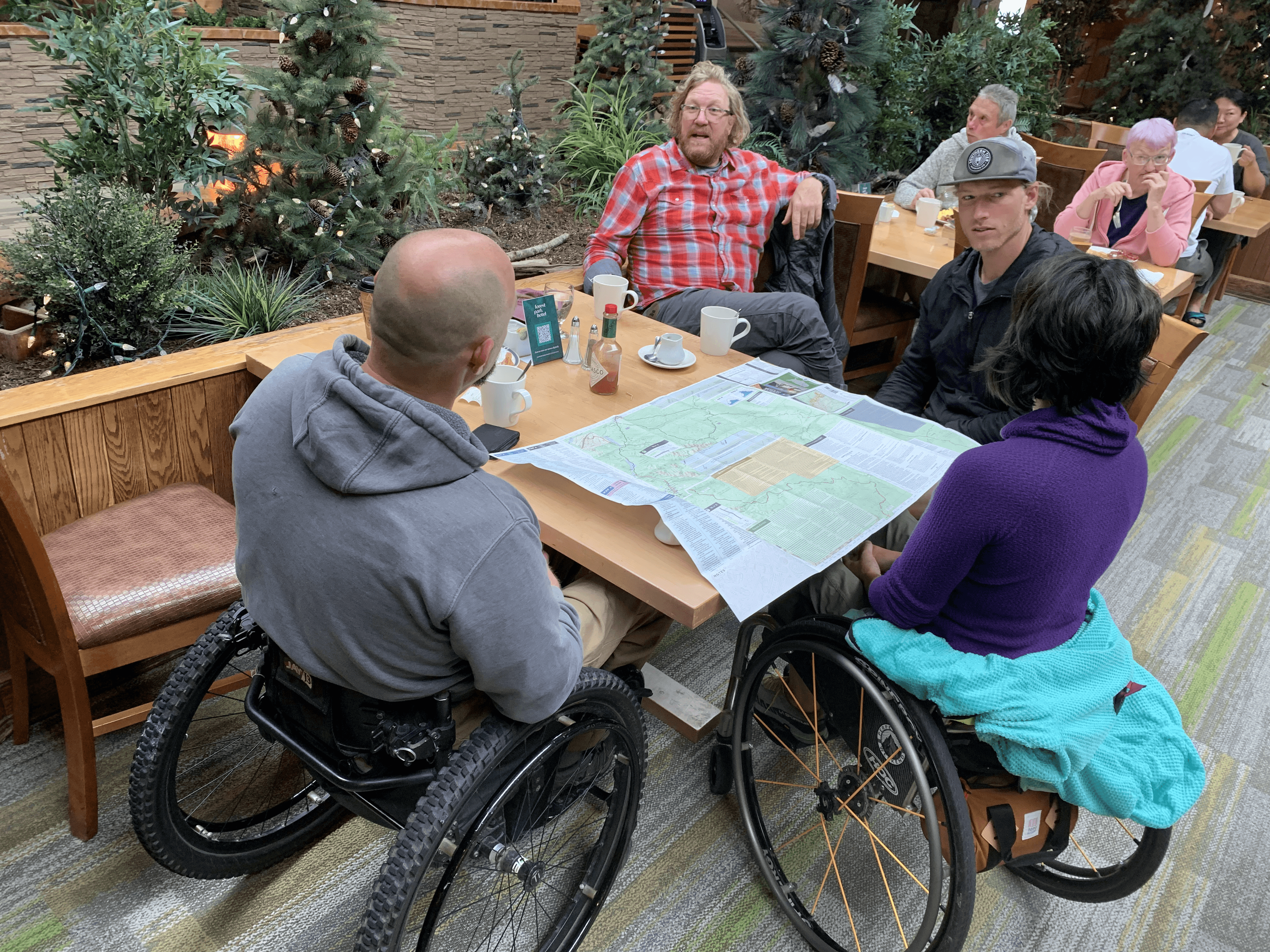

Karl (upper left) sitting next to Robbie Prechtl (upper right) as those two help Quinn and I strategize our Trail Divide excursion back in 2022.

Karl came back after giving me some privacy to cath and looked at the scene in horror. I told him I needed to get to a hospital. The clock was ticking on my bladder and I was certain I couldn’t cath again without causing more damage. It was a pretty scary moment.

After pleading my case through spotty rural cell reception, I was fast-tracked to a urologist without a referral. I arrived at the clinic an hour later. The doc saw all the blood on my pants, listened to my story, and said I may have created a “false passage.” This is a very friendly way of saying I may have poked the catheter through my urethra and into the void of my body.

After the long, awkward moment of laying on the exam table with my pants down in front of two women I’d just met, the doc and her assistant pulled out a cystoscope, which is a long cable with a camera at the end of it. Into my unmentionable they plunged and, to our relief, found that I had only torn my urethra. They sent a wire into my bladder. This was a placeholder and guide for a Foley (in-dwelling) catheter which, once inserted, was to remain there until my urethra healed.

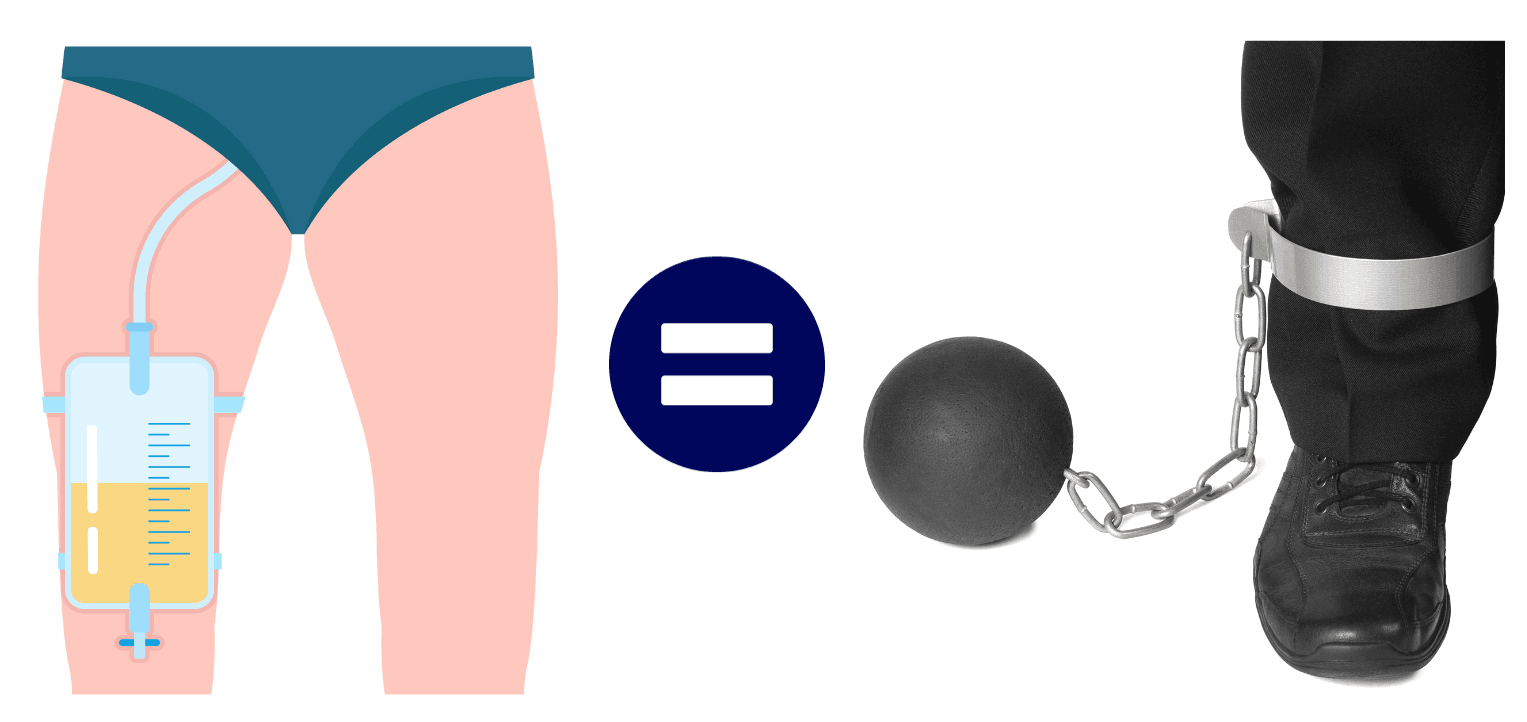

To put it mildly, this situation majorly cramped my style. I remember using a Foley in the early days of my injury, but had forgotten what a pain in the ass it was. Now, whenever I lay down or get up I need to think through the order of operations for dragging this urine-filled anchor around my house and my life. It’s difficult to sit up because, having bladder sensation, I feel the urge to to pee all the time. Then my bladder gets pissed off and starts to spasm. It feels like my bladder is on a stretcher.

Caring for this anchor also takes about an hour out of my day. I have to clean and replace the bags, night and day, and irrigate my bladder to avoid a blockage by blood clots. All of this when I just want to go to bed. It also means that I have to put on hold all the important physical things that are necessary to my family and my health, like making progress on building our home and going to the gym to stay healthy.

For me, the cost is a week of major inconvenience and fear that this problem will continue. But what about my SCI friends who live with an indwelling catheter? What about the people who have to live their lives, day in and day out, with this thing hanging out of their bodies? This thing - that requires so much maintenance and gives the gift of regular urinary tract infections? And this is only one of many complications of living with an SCI!

This experience was a reminder of what I’d forgotten. I am a prisoner to this condition. There is nothing I or any other para or quad can do to escape it. As a coping mechanism, we adapt. Our brains cannot remain in such an intense state of panic, so we grow accustomed to the situation. It wears us down like water dulls the sharp edges of a rock.

Despite its importance for daily survival, adaptation can also be the death knell for activism. We adapt and forget and move on with our lives because there is no other choice.

As it relates to my own activism, I’ve adopted a mindset of cognitive dissonance to make room in my head for the coexistence of two, apparently competing, ideologies. On one hand, I have to pursue a fulfilling, positive, satisfying life. It’s the reason I take on challenges like going rim-to-rim on an adaptive trike in the Grand Canyon. It’s also why I play music and regularly enjoy the company of friends and family. On the other hand, I need to remain frustrated and dissatisfied with the state of cure research until there are meaningful answers for our community.

Sometimes dissatisfaction is a choice - a conscious act to see things as they really are. And sometimes - especially when you have an SCI - it explicitly drops back into your lap as it did for me this week. For a moment I was forced to shed the veil of adaptation; to see the reality of this injury afresh.

Yup, that's me (left) speaking on an advocacy panel at U2FP's 2022 Symposium with our board member Barry Munro (center) and fellow CAN Manager Jake Beckstrom (right).

There has to be a better way. Why are we still living like this? Why have we not solved this problem? Why have we not solved ALL the problems of SCI? Why is there no urgency?

These questions often overwhelm me. The only things I know to do about them, right now, are to listen to my peers, seek out where progress can be made, show up and speak up. That is why I value our advocacy with U2FP.

I need to pursue joy and passion in my life. But I also need to remain dissatisfied. I don’t have to rot away under caustic militance but I need to remember, there is no cure, there is no escape...Yet.