February 12, 2025

Headline Patrol: Brain Stim Restores Walking in Paralyzed Patients

Sam Maddox

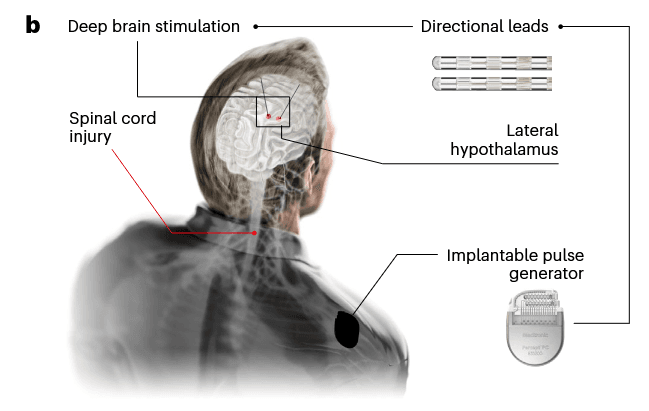

Here is a recent news story about a brain therapy that allowed two paralyzed individuals to walk again. By stimulating a part of the brain called the lateral hypothalamus (LH), scientists in Switzerland reported meaningful recovery in two individuals with incomplete spinal cord injuries.

Above: A clinical trial participant, Wolfgang Jäger, gets out of his wheelchair and climbs up and down the steps using the deep brain stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus. (.NeuroRestore / EPFL)

The pilot study, “Hypothalamic deep brain stimulation augments walking after spinal cord injury,” was recently published in the journal Nature.

This paper was authored by scientists Jordan Squair and Nathan Cho and colleagues from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (EPFL), Lausanne. This is the research home of Gregoire Courtine and Jocelyne Bloch, who oversaw this work as co-directors for the .NeuroRestore centre; they are pioneers in spinal cord stimulation and authors of several high-profile “paralyzed man walks” papers in recent years.

Model showing the lateral hypothalamus undergoing deep brain stimulation (© 2024 EPFL)

What’s What

Below is a quick overview of this fascinating study, addressing its key features and pondering some inherent limitations.

What’s important to note? The two individuals enrolled in the study could already walk some. One was 29, five years post injury, classified as a T1 motor and sensory incomplete (AIS C); the other was 51, 16 years post injury, C5, also incomplete (AIS D).

What about rehab? Yes, very important. Both underwent a post-surgery, three-month structured rehabilitation program that showed, per the paper, “pronounced improvement” in walking – without brain stim.

What about complete injuries? Sorry, this kind of brain stimulation won’t work if there’s no residual nerve activity. As Courtine noted in the EPFL press release about this study, “This research demonstrates that the brain is needed to recover from paralysis.”

What’s cool? Both participants gained function and walking speed. Both achieved their respective rehab goals: one to walk without orthoses; the other to climb stairs independently. Both participants also showed long-term gains that remained even when the stimulation was off. This suggests that brain stimulation plays a role in reorganizing residual nerve wiring for sustained neurological improvement.

What’s new? Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is rather common. It was first approved in 1997 for treating tremors, then in 2002 for Parkinson’s disease, and in 2009 for obsessive compulsive disorder. This is the first time DBS has been shown effective in humans to enhance function after SCI.

What’s unique? In this case, DBS activates a part of the brain, the lateral hypothalamus – the LH – that has not previously been specifically targeted for motor function. Another section of the hypothalamus, the posterior area, has been stimulated with DBS since 2000 to treat chronic cluster headache.

Figure b from page 7 of the paper, illustrating the main components and affected anatomy of the procedure. (Cho, N., Squair, J.W., Aureli, V. et al. Hypothalamic deep brain stimulation augments walking after spinal cord injury. Nat Med 30, 3676–3686 (2024).

Until now, motor function studies in SCI, and the primary clinical use of DBS, have targeted an area of the brain related to motor commands, the mesencephalic locomotor region (MLR).

What surprised the EPFL investigators? The LH has scant mention in the science literature as a motor function center. Indeed, the hypothalamus is generally regarded as a regulator of behavioral and physiological processes including feeding, arousal, stress, reward and motivated behaviors.

What about more participants? The EPFL is recruiting people with chronic SCI able to walk independently for a few steps with a walker, continuing the DBS clinical trial. See details here.

What’s more? Another human trial, “Deep Brain Stimulation in Patients with Incomplete Spinal Cord Injury for Improvement of Gait (DBS-SCI),” also in Switzerland, is recruiting five participants. This one is from Balgrist University Hospital, Zurich, with principal investigator Armin Curt. The study will use DBS on the MLR region, which in preclinical animal studies was shown to amplify nerve circuits to improve motor function after SCI.

What else? So readers have a bit of context, this DBS project was based on precisely locating the set of cells in the hypothalamus that relate to movement. This was done by constructing a detailed atlas of the brain, guided by genetic cues, advanced microscopy, and data mashing.

From the paper:

"Central to this discovery were reproducible anatomical, imaging and computational methods that enabled us to elaborate a space–time brain-wide atlas of recovery from SCI. These methods supported the comprehensive survey of every region of the mouse brain during the [spontaneous] recovery of walking after incomplete SCI. We combined this survey with rational neurobiological hypotheses based on the known anatomical and functional patterns of recovery following incomplete SCI. Unexpectedly, this analytical framework nominated a single region of the brain that fulfilled all our a priori neurobiological hypotheses."

To the surprise of the team, the lateral part of the hypothalamus responded best.

The detailed brain scans guided placement of tiny DBS electrodes. The patients were fully awake during this part of the surgery. Neurosurgeon Jocelyne Bloch had this to say about the surgery, from an EPFL press release:

“Once the electrode was in place and we performed the stimulation, the first patient immediately said, ‘I feel my legs.’ When we increased the stimulation, she said, ‘I feel the urge to walk!’ This real-time feedback confirmed we had targeted the correct region, even if this region had never been associated with the control of the legs in humans. At this moment, I knew that we were witnessing an important discovery for the anatomical organization of brain functions.”

Lead Author Interview

I had the following exchange with co-author Jordan Squair (who is Canadian, by the way, not Swiss) about the EPFL DBS study.

Above: Jordan Squair, senior scientist at EPFL’s .NeuroRestore Center and one of the lead authors on this study.

First, the paper is well written; it lays out the hypotheses, the experimental plan, the methods, the results. If you deserve any credit for that, speak up!

Thanks very much! Yes, I wrote the paper with Gregoire, Newton, and Jocelyne.

Second, this study makes a difference. There was recovery in incomplete SCI patients. Meaningful, and apparently safe. How does the lab frame this – just how significant do you guys think this is?

The recovery we saw in the two patients included in the trial were among the biggest we have ever seen. It is important to consider these are incomplete patients, who likely also partially benefited from the rehabilitation. But we are very excited to move towards the next steps of understanding who will benefit most from this therapy.

Let’s start with the lateral hypothalamus, the LH, an interesting part of the brain. As the paper notes, this area is historically associated with arousal – I read about how LH stimulation tapped into a “copulation-reward center” that made male rats super horny, and that the hypothalamus has been clinically targeted for obesity and cluster headaches.

Yes, it has historically been thought to be involved in motivated behaviors - an important consideration for any future trials.

There was at least some link in the literature between the LH and movement, going back 35 or 40 years. Can you describe the surprise as your neuro cartography turned up the LH as it relates to movement?

Yes, we were able to find some old papers describing some involvement in movement [in the LH], so we thought we would then investigate whether it was true or not! We were definitely surprised. After doing the analysis, it was clearly the LH region fitting all our hypotheses more than anything.

It may be asking a bit much of our readers to follow the complex imaging and mapping procedures. How much of that were you personally involved with? Can you give us a shorthand take on how iDISCO and CLARITY work? And maybe light-sheet microscopy?

My role in this work was primarily on the computational side. These tissue clearing techniques [iDISCO and CLARITY] were developed by Karl Deisseroth at Stanford about 10 years ago and since then have become extremely important in neuroscience. The different methods allow us to remove the lipids from the tissue and image the entire brain without cutting it by using these [light-sheet] microscopes that have excellent penetration through this 'cleared tissue'. Effectively, this really allows us to do 'whole brain' analyses quite quickly as opposed to having to cut and stain hundreds of sections (which can take months to years).

The use of optogenetics is quite fascinating, and the result is a space-time mapping schema that allowed you to then substitute DBS to turn up the volume on the movement response. Is this part of your work?

The optogenetic results were really encouraging. All these experiments were done by Newton Cho.

From what I read in the paper, you wanted first to make sure the LH is indeed activated during human walking, using healthy subjects and functional MRI. It was indeed active. So you went right away to test DBS in transected mice, and then to an SCI contusion model in rats. And the LH stim worked. This would be the time to publish those preclinical results, but that was not the case. It appears your team was motivated more toward a human clinical trial.

We did not publish the results until we understood whether this could work in humans. We try as much as we can to make the full link (from animals to humans) for each project if it is feasible. In this case we felt the results were so profound in the animals that it was worth it to launch a clinical study.

Did you personally have interaction with the two participants? They are obviously thrilled; they got what they hoped for. As noted in the paper, you anticipate that not everyone will respond as these two participants did, so many more people will need to be implanted with DBS.

Yes, I had some interaction with the patients. This is a huge strength of .NeuroRestore and us being able to take the things we learn in rodents and test them in clinical proof of principle or feasibility studies. Next, we need to do more patients to understand who will best respond.

Is there a possibility this type of brain stim could have downstream effects that were not anticipated, e.g. one can imagine seeing weight loss, or reward seeking.

Yes we will certainly need to do good hormone tracking to understand any potential side effects (which we did in these two participants). And all our clinical studies have ethical approval and oversight.

Any good news here for SCI completes? Any consolation for them?

For complete SCI we will need regeneration. This therapy will require some degree of spared motor function.

The Wrap

Are we on the verge of electroceutical medicine? This study shows that with better tools and better precision, targeted brain stimulation can very much improve spinal cord injury outcomes. As the molecular biology of movement is explored, it’s reasonable to expect more discoveries in more parts of the neural anatomy. One can imagine having a scanner of some sort to customize a neural map for each individual and then optimizing stimulation from a suite of device choices.

We’ll continue to follow the Swiss EPFL group and other labs around the globe as they explore the brain and spinal cord and the effects of neuromodulation.

Stay curious.