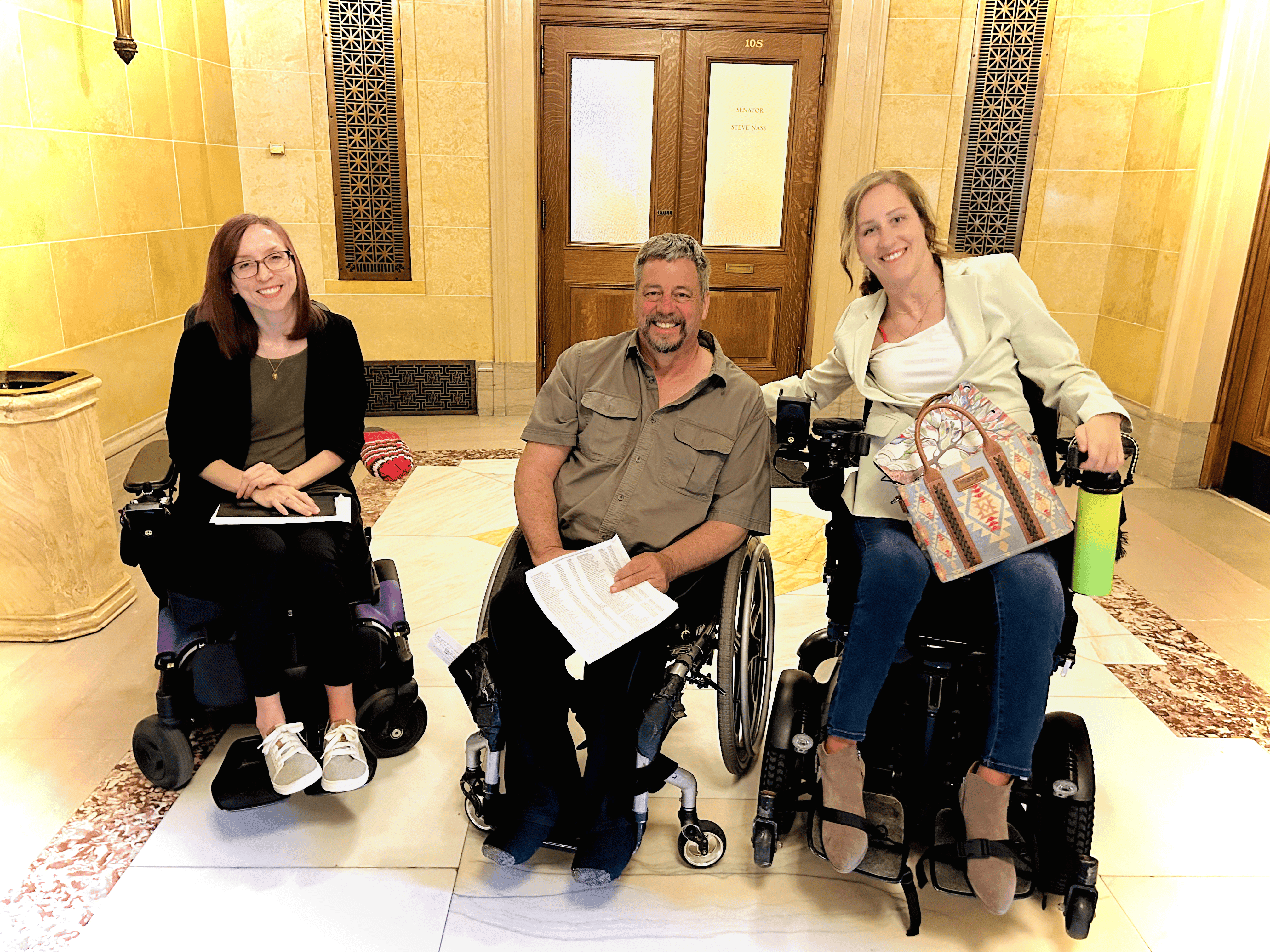

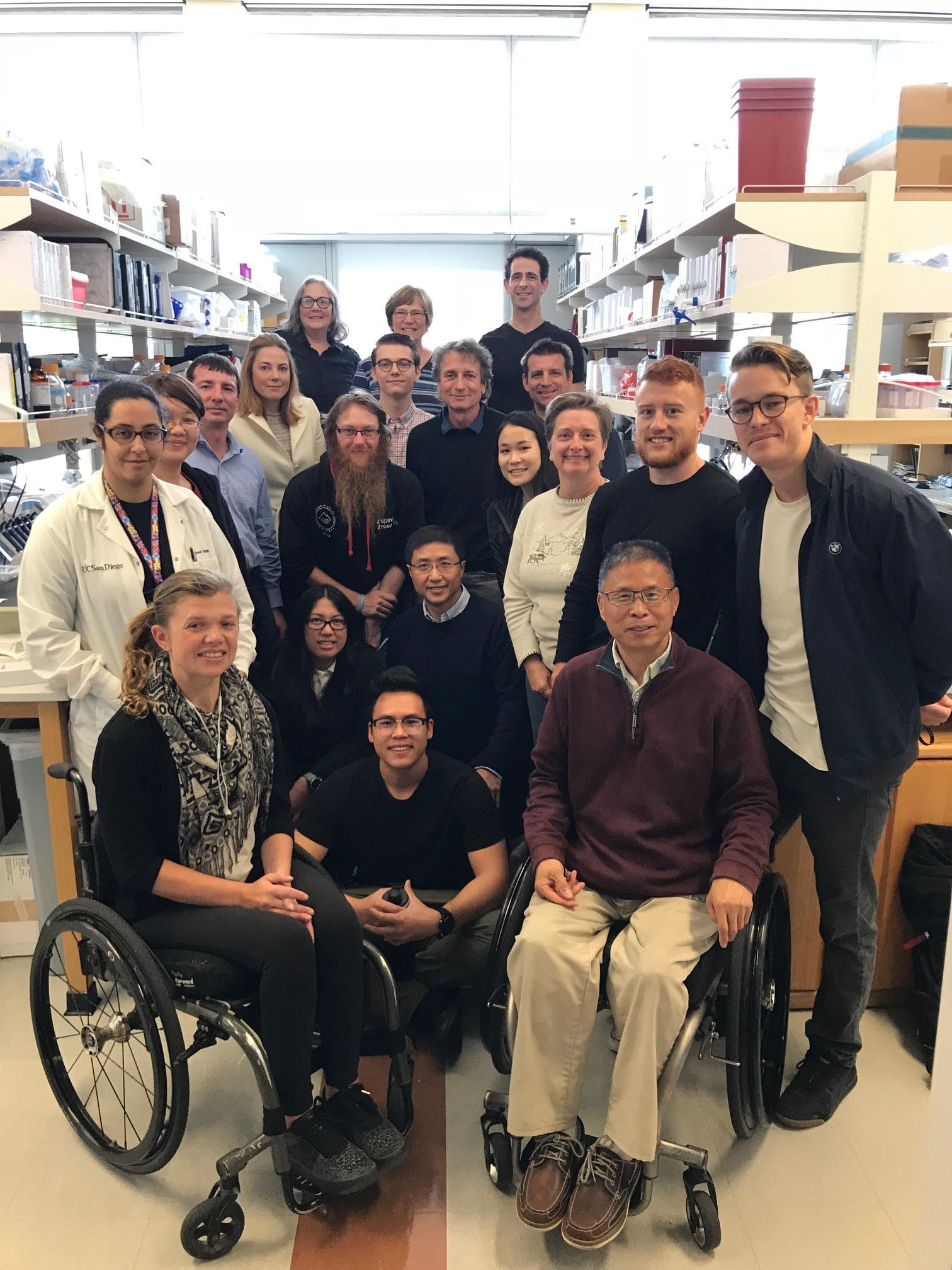

Eric Keeler (right-middle, bearded) welcomed to San Diego by members of the Tuszynski and the Zheng lab. Keeler ran from corner to corner of the United States to raise money and awareness for spinal cord research.

. . .

This is the first in an on-going series of posts by our new contributing science writer, Alina Garbuzov. Alina holds a post-doctoral position in Mark Tuszynski’s lab, and has a SCI. She will be exploring scientific developments in the spinal cord injury field in order to drive smart decision-making both for personal health and for setting research goals. Read her full HERE.

If you have a spinal cord injury, you need to know more science than the average, able-bodied person. Specifically, you need to know neuroscience and some basic biology. I’ve learned this as an SCI patient three years out from my injury; and as a biologist who now works in a spinal cord injury lab. While I believe all citizens need to have a basic scientific understanding, I would argue that if you are facing a difficult diagnosis, such as SCI, you need science even more.

Below are three reasons you should become an armchair neuroscientist.

1. You need to be able to communicate intelligently with your doctor about your health care decisions.

An injury to the central nervous system permanently affects most of the functions in our bodies. We need to deal with changes to the immune system, with autonomic dysreflexia, with chronic pain, and with depression. The difficulty and the complexity of the problem means doctors often fall short. Even with the best health coverage money can buy, we may end up shuffling from expert to expert, still without answers and struggling to understand what is going wrong.

The best answer, in my opinion, is to become your own advocate. To gather all the knowledge you can and start directing your own care. You'll be able to go to your doctor with the right questions and understand what is known and unknown about the cause and treatment of your symptoms.

The importance of scientific education is also supported by a recent study of chronic pain with SCI[1]. One of the major conclusions from this survey of ~500 people living with SCI and chronic pain is that “poor health care communication,” is a top common barrier and that SCI patients " ...do not receive adequate information from their health care providers regarding pain".

2. Protect yourself from the snake oil salesmen.

If you understand the basics of the nervous system, you'll begin to discriminate between the cutting-edge treatments that may work for you and the pseudoscience.

The peddlers of fake cures know that people with SCI are desperate for a fix. This makes us vulnerable. Protect yourself with education.

I know too many people who think that drinking pH 8 water, “grounding”, or injecting yourself in the arm with mesenchymal stem cells is beneficial. Should you travel to India for a therapy not approved in the US? Should you take a drug that's been shown to improve walking in MS patients?

It's impossible for doctors to keep up with all the latest research. If you want answers to hard questions, you have to do the digging yourself.

Similarly, if you want scientists to study the problems that are most important to you, you're going to need to understand the field.

Interested in a treatment for autonomic dysreflexia? Are we stalled because there is not enough understanding of the basic cause? Or is there a promising treatment in rats that has not been tested in monkeys or humans? Knowing what's missing -- even in broad strokes -- is key for effective, targeted advocacy.

3. Becoming an Armchair Neuroscientist will allow you to prioritize the agenda for SCI Treatments.

There are channels we can use to set the agenda. One of the most cited papers from the Journal of Neurotrauma is Professor Kim Anderson’s “Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord-injured population”[2]. This survey of people living with SCI details our priorities for recovery. I’ve personally seen this paper’s figures, showing an emphasis on hand function and bowl/bladder/sexual function, presented many times at conferences and cited in scientific papers. Scientists do care, deeply. Each one I’ve interacted with is willing to listen, wants to know how they can make the biggest impact and is motivated by making a difference.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) -- the biggest source of grant funding -- is required to listen. Their job is to represent us, after all. Congress determines how many total dollars go to the NIH. But how those dollars are allocated is mainly based on input from scientists and patient groups. There is a direct line of communication open to us. Do you want more funds allocated for SCI research? Or should we be using more of that funding to study chronic pain? The government has set aside a pot of 76 million dollars for research that benefits people with spinal cord injuries. This resource is for us. Our voice can be used to shape the agenda in university labs around the country and the world. But we'll need a basic understanding of the science in order to join the discussion.

Stay tuned for a follow-up post from Alina that will include solid resources on where to get started, how to navigate the daunting landscape of scientific research on the internet, and some suggestions for keeping a balanced perspective through it all.

Join us,

Alina Garbuzov, Contributing Writer | Postdoctoral Researcher

U2FP | Center of Neural Repair, Mark Tuszynski Lab at UCSD

Citations:

[1] Eva Widerström-Noga, Kimberly D. Anderson, Salome´ Perez, Judith P. Hunter, Alberto Martinez-Arizala, James P. Adcock, Maydelis Escalona. (2017). Living with chronic pain after spinal cord injury: A mixed-methods study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Volume 98 , Issue 5, 856 - 865 | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27894730

[2] Anderson, K. (2004). Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord-injured population. Journal of Neurotrauma, 21(10), 1371–1383. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15672628 | (note: this article is behind a paywall, but you can e-mail Professor Kim Anderson to request a copy)