In the wake of our Symposium, with all of its detailed strategies for scientific and advocacy advances, we wanted to re-center the personal experience of those who live with the injury. I am one of those people. I shared this reflection on my injured anniversary with my friends and family this past August. I hope it resonates with those who are injured, and motivates all those working for a cure.

Sixteen years.

That’s five thousand eight hundred and forty-five days since my injury.

I was sixteen years old when I crushed my spinal cord.

And it has been sixteen years since.

I had sixteen years of a life with unlimited possibility and an unnoticed ease of physically doing anything I wanted.

I want to climb that tree - I climb that tree.

I want to live outside for a whole summer - I live outside for a whole summer.

I want to dive in that pool - I dive in that pool.

And since then, I’ve had sixteen years of life with an open and glaring inability to physically do most of the things I want to.

Sixteen years since I was last able to do a million things.

Since I was last able to snap my fingers.

Like snapping your fingers is anything special.

Except it is special.

It is special when you can no longer do it under your own volition.

What I wouldn’t give just to be able to snap my own fingers.

Snap. Do it yourself, right now, as you read this.

Snap.

Something as simple as that. Just to be able to do that. It would be life changing.

Five thousand eight hundred and forty-five days.

And counting.

Yet it’s not just wanting to snap my fingers. To once again be able to control my wrists, hands, and fingers.

It is a wanting to do everything I was never able to do.

Everything that had laid before me, ripe for the plucking, on the eve of the prime of my life.

There is a yearning. A deep and ever-hungry desire to return to my former self.

One who could do anything - without a second thought.

Able to experience and feel, without even realizing that I was ABLE to experience and feel all that was present in reality.

And now, when I truly want to feel the physical sensation of touching something, I must concentrate my entire focus on that one part of my body.

In a vain attempt to awaken the nerves there. For them to collect the sensation and send it to my brain, to tell me what it feels like.

To feel the softness of my golden retriever’s ear as I pet him.

To feel the caress of a girl’s hand on my knee.

To feel all the sensations and pleasures of making love.

I pour my entire being into that one point, only for it to return to me a facsimile of a facsimile of the real sensation.

Like attempting to tune into a radio station that is just out of reach of the receiver.

You are only able to catch a fleeting word here and there, through a hiss of static and buzz before the signal is lost.

And in that moment, you can almost trick yourself into hearing the ghost of the voice that was faintly coming through. But no, it is gone.

Yet the loss of sensation and feeling is not even that big of a deal. It is just one small piece out of a million small pieces that I have lost.

Don’t get me wrong. I love my life. I am happy to be alive. I am currently living a full and happy life.

I am so grateful for all my family and friends. So grateful for every single person who loves me.

It is just the loss of the potential of living a fuller life that haunts me.

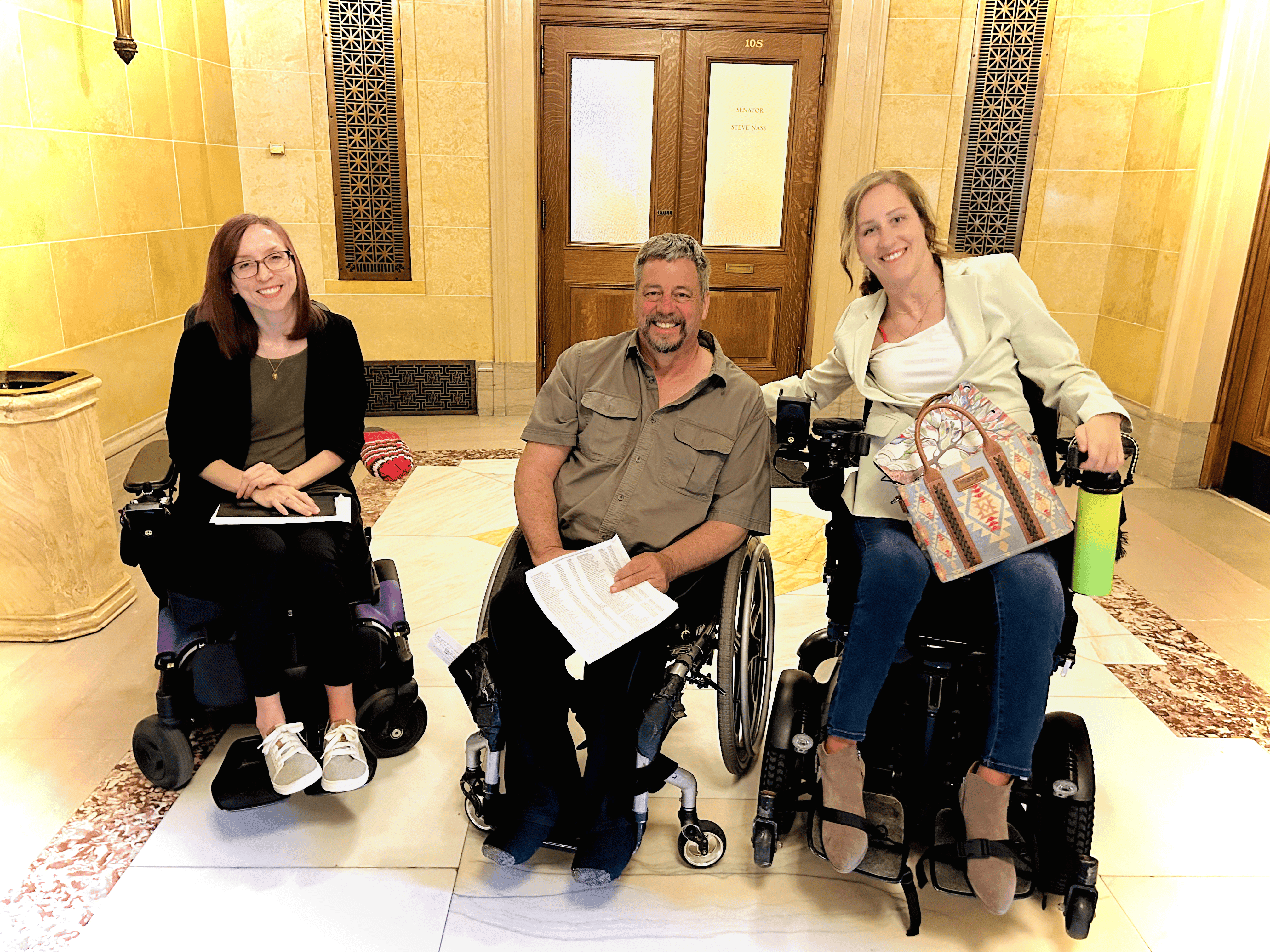

I don’t want this post to come off as me whining about my situation. There are tens of thousands of other people in this country who have the same injury as me, the same loss of function and sensation as me, the same problems and difficulties as me, and who are forging ahead nonetheless, because that is what you must do.

Hell, there are tens of thousands of other people who have a higher injury than me, have worse problems and difficulties, and who carry on just the same.

I am only writing this to commemorate a mile-marker in my life. The point at which the majority of my life is transitioning from being an able-bodied person, to that of being a disabled person.

Some people are able to embrace their new reality after an injury. To accept their new identity as “someone who is disabled,” or “someone who uses a wheelchair.”

I was never one of those people.

Even though that is exactly who I am.

I think my resistance to this acceptance is due to my reluctance of acknowledging that loss of potential from my former life.

As if I can still cling to it, if only I do not acknowledge that it is not there.

I know that my current situation affords me plenty of potential to do many worthwhile things that will make me happy and continue to fulfill my heart and soul. I have before me many worthwhile things that will make others happy and fulfilled, and that will make the world a better place.

It is just that my current potential is so much more limited than what I had prior to my injury.

I do not scroll through Facebook that often. Because I will inevitably see posts and photos from my high school and college friends, and other peers my age.

They post pictures of themselves

scuba diving the Great Barrier Reef

climbing the glaciers of the highest Alps

getting married and having children.

And eventually, I cannot help but begin to think about what types of pictures I would be posting had I never gotten injured.

I know that I can still do many things. With the help of all the people in my support group surrounding me, I can still do many things that I truly love.

But there is a difference between doing something only with the help of others, and doing something, creating something, becoming something on your own, with no one else’s input, except your own grit and moxie.

All my potential is captured in those photos of my peers living out their able-bodied lives. All those possibilities were in my hands, were in my future.

And it’s not the fact that I took that potential and those possibilities for granted. There’s no denying that I took all of it for granted. That I did not appreciate what I had, when I had it.

It is the fact that all that potential was taken from me without my consent.

Lost forever.

And yet, would I change it if I could? Go back to that night sixteen years ago and not dive headfirst into the pool?

This I cannot definitively answer.

Some days the answer is an emphatic YES!

Other days, the answer is a plain no.

I don’t know what point I am trying to make by writing this. But here I am.

Currently, Rudyard Kipling’s poem “If” comes to mind.

Paraphrasing the section of which I am thinking does not do it justice, but suffice it to say:

My heap of all my winnings had certainly been lost.

But I must forget about what was had, and what was lost.

And if I can do that, then the Earth is mine and everything that’s in it.

Sixteen years before my injury.

And sixteen years since.

Five thousand eight hundred and forty-five days.

And many more days and years to come.