Everyone has an idea in their head what clinical trials are – the use of humans to test a drug or device therapy with the goal of moving it toward what we call translation: get an idea, study it, try it. If it works, bring it.

There are more trials for spinal cord injury related issues now than ever – fewer than 10 in 2012 to 112 in 2021 – and more are coming. But not a single one has led to a treatment. There are many reasons for this: Drugs or devices just didn’t work as they did in animal studies, sponsor companies ran out of money, etc. But it’s not just hard science and lack of resources: There are issues with the way trials are designed, reported, and tracked. Let’s explore this important part of the treatment pipeline.

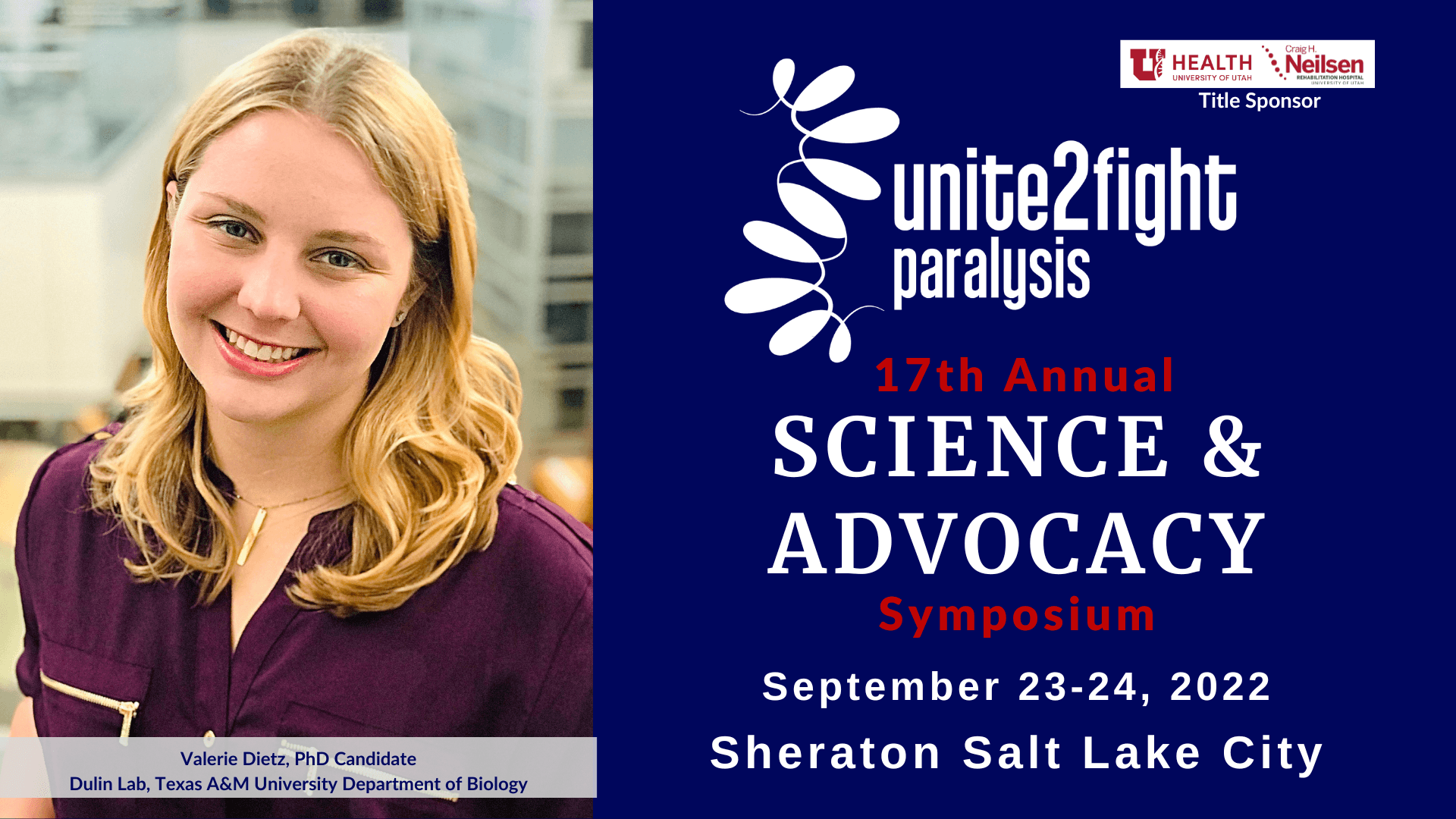

Upcoming at the Unite 2 Fight Paralysis 17th Annual Science and Advocacy Symposium in Salt Lake City, Saturday, September 23: PhD candidate Valerie Dietz from Texas A&M University presents a talk, “Fighting for Recovery on Multiple Fronts: The Past, Present, and Future of Clinical Trials for Spinal Cord Injury.”

Dietz’s talk is based on a paper of the same name that came out last week in Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience from Dietz and a group in the A&M lab of Jennifer Dulin. Six members of the SCI community consulted on the paper, including U2FP Executive Director Matthew Rodreick, Chris Barr, Jesus Centeno, Scott Leininger, Kent New and Peter Nowell. Several of the group had participated in clinical trials.

Dietz and Dulin are basic scientists who study cells and molecules and neural circuitry. Their job is to try to understand what’s going on in preclinical injury models (animals), not to work out strategies to move their results from lab to clinic. Dietz: “We do however want to understand how science is translated to people who benefit, so we decided to take a look at one aspect of this process: spinal cord injury clinical trials.”

There was no broad overview, so they created one. From the paper:

Currently, 1,149 clinical trials focused on improving outcomes after SCI are registered in the U.S. National Library of Medicine at ClinicalTrials.gov. We conducted a systematic analysis … we categorized each trial according to the types of interventions being tested and the types of outcomes assessed. We then evaluated clinical trial characteristics, both globally and by year.

Gaps: incomplete, user unfriendly

Clinicaltrials.gov is inconsistent, incomplete, and not user-friendly. “It forces users to make assumptions,” said Dietz. This gap really sticks out: Over 75 percent of clinical trials with “Completed” status do not have results posted. Some results are published, but behind journal paywalls – inaccessible to the public. From the paper:

It is crucial that the public, scientific and clinical community be able to see results of clinical trials so that informed decisions can be made moving forward and integrated into the decision of participation, funding and approval of future clinical trials.

There is no curation moderator at the National Library of Medicine who makes sure that a trial listing is followed up with results. But why not? Dietz and her co-authors say fully transparent data sharing and results reporting, good or bad, should be required.

Out of phase: other issues identified

We found that inconsistent or inaccurate application of FDA phase status, as well as the absence of sequential or graduated trial strategies, suggest that most trials do not appear to be designed to progress toward FDA approval.

Wait a minute, if a trial was never meant to be FDA approved, or leave the lab, what was it good for? Does this mean some trials are designed as human neuroscience research to answer scientific questions without intention to get to clinical practice? Or does it mean that some trials are carried out mainly to burnish an academic career profile?

Is the trial a potential therapy, or not?

… a designation labeling interventional SCI trials as “therapeutic” versus “not therapeutic” would be helpful; we found that 2.62% of SCI clinical trials labeled as “Interventional” were not actually testing a therapeutic intervention, and it would be useful for SCI community members to easily identify trials of therapeutics.

There is duplication – but how much?

… it is unclear how much conceptual or programmatic overlap exists among clinical trials testing very similar interventions (e.g., neuromodulatory interventions for locomotor recovery), so some cross-referencing to indicate relationships between trials that are testing the same device, or trials that are otherwise linked in scope, would be useful.

Does anyone speak the same language: How about sharing some common ground here? Dietz et al. want to “harmonize/standardize data elements so that comparisons between trials can be made.”

Wanted: Efficiency. And how about combination trials?

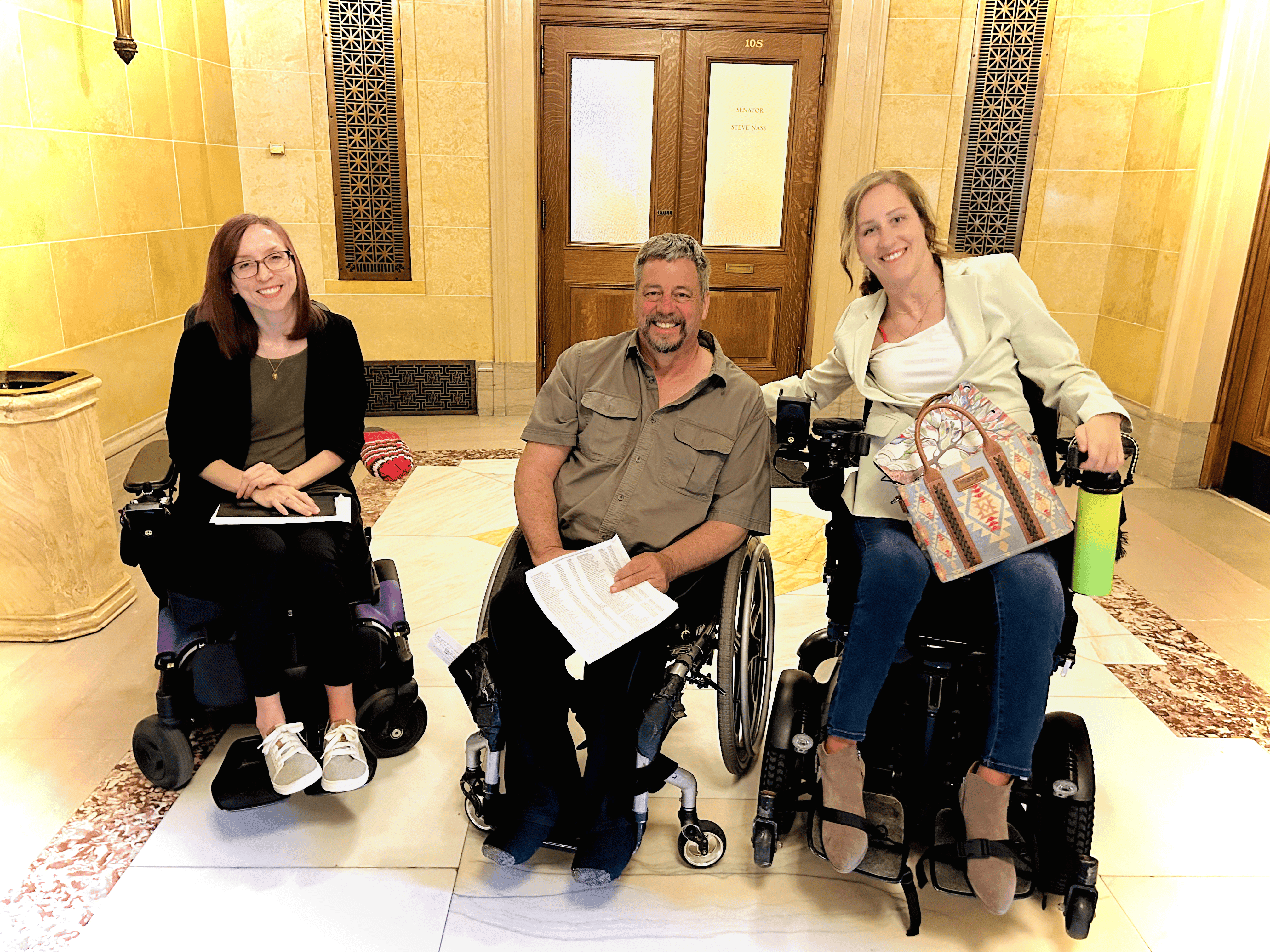

Chris Barr helped Dietz dig in to the data. He has spinal cord injury trial experience, having been the “super responder” in a 2019 Mayo Clinic stem cell trial. He notes these gaps:

- Four in five trials are designed to address the symptoms of SCI, not cure. Half of those are stimulation trials where there appears to be significant duplication – each stimulation trial shares the same objective and intervention method. “With so much duplication,” Barr asks, “Is there a risk of redundancy and possibly an opportunity for communication and improvement in efficiency?”

- There are few true combinational trials. Said Barr, “There isn't a single trial that combines the two most promising therapies: stem cells and neuromodulation.”

Barr likes the idea of a ClinialTrials.gov registry – to allow individuals to upload their personal data and injury specifics to be matched with relevant trials. That is already possible to some degree by way of two curated SCI trial resources: SCITrialsFinder.net and SCITrials.org.

Dietz’s presentation will applaud the increasing partnership between individuals with SCI and the research process (note the Symposium workgroup panel “SCI Research Advocacy Course and How to Become a Research Advocate,” led by Barry Munro, Canadian/American Spinal Research Organization, North American Spinal Cord Injury Consortium).