Jan 27, 2026

Headline Patrol: Recovery via 3D Printed Cell Scaffolds

Walt Schumacher & Sam Maddox

Ed. Note: Schumacher, the lead reporter for this story, is part of a group of writers I am mentoring to add new voices to the Headline Patrol. If any readers would like to join us, to learn about science journalism, and to deep dive into SCI research, contact me at sammaddox@u2fp.org.

Walt Schumacher is a T5 complete paraplegic injured in a dirt bike accident in Moab, UT in 2024. Last year, Walt received an epidural stimulator implant and participated in a clinical trial at Kessler Institute. He regained volitional movement of his legs and the ability to take independent steps on a treadmill. Says Walt, “The field of spinal cord injury research has a long way to go, but there is a lot of good work taking place and progress is being made.”

Breakthrough in 3D-printed scaffolds offers hope for spinal cord injury recovery. That’s a headline from the University of Minnesota (UM) public relations office detailing a recent UM study (full paper here) using silicone scaffolds seeded with stem cells to form spinal cord-like structures. Implanted in animals with spinal cord injuries, these organoids promote what principal investigator Ann Parr, MD, PhD, describes as significant motor recovery.

Hundreds of stem cell studies have been conducted targeting spinal cord injury repair for over 20 years, including numerous human trials. There have been hundreds of claims for functional efficacy, too. So far, though, no cell type (neither embryonic, mesenchymal nor genetically induced stem cells) has had the predictable therapeutic effect to justify the headline writer’s favorite term, “breakthrough.”

Stem cells haven’t met the SCI community’s high expectations. For one, stem cells, by themselves, may not be molecularly specific enough to affect recovery. Fat cell or bone marrow cell derived stem cells (mesenchymal), or embryonic brain cell-derived precursors, affect certain features of SCI pathology but may not embody the necessary therapeutic ingredients to restore nerve to muscle function.

(For a thorough overview of cell therapy and SCI, see the recently published review paper, Stem Cell Therapy for Spinal Cord Injury. One takeaway:

. . . many preclinical studies and a growing number of clinical trials found that single-cell treatments had only limited benefits for SCI. SCI damage is multifaceted, and there is a growing consensus that a combined treatment is needed).

Location matters too. Generally, the implanted cells need to be close to the damage in the spinal cord – but they don’t always stay where they are injected. They need an adequate support structure.

Spinal cord scaffold technology is a very active field, covered in this space and at the U2FP Symposium in the recent past:

- InVivo trial – ten patient trial of an implanted biodegradable scaffold “did not produce probable clinical benefit;”

- Amphix, a company based on Samuel Stupp’s nanostructure dancing molecules. is advancing toward clinical trial;

- UC San Diego 3-D scaffolds study, “. . . here we demonstrate host axon regeneration entirely beyond a severe, complete spinal cord transection site supported by a bioengineered scaffold.”

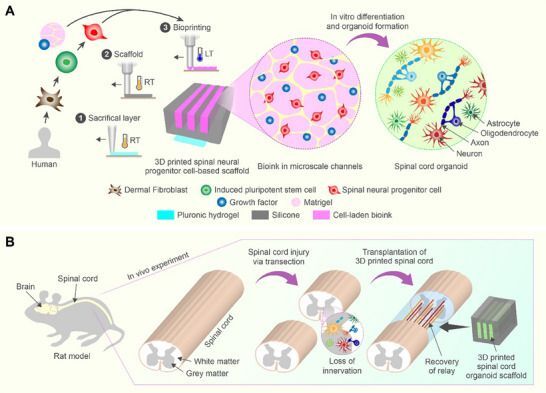

This new University of Minnesota study attempts to address both biology and engineering. They start with genetically derived spinal cord progenitor cells that have been grown into organoid tissues. The tissue is seeded on a channeled scaffold about the size of a rice grain. The scaffold helps the cells survive and directs them to integrate with surviving spinal cord tissue.

Still image from a video showing the process of building the 3d printed scaffold for treating spinal cord injuries (College of Science & Engineering, UMN).

From the published paper:

The scaffolds direct axonal projections along the channels and guide the cells to simulate in vivo‐like conditions, leading to more effective cell maturation and the development of neuronal networks crucial for restoring function after SCI. The scaffolds, with organoids assembled along their lengths, are transplanted into the transected spinal cords of rats. This significantly promotes the functional recovery of the rats. At 12 weeks post‐transplantation, the majority of the cells in the scaffolds differentiate into neurons and integrate into the host spinal cord tissue.

The layer-by-layer 3-D printing process is quite fascinating. Each silicone scaffold unit has three channels; the spinal cells are layered on those, as a bio-ink of sorts, as you can see in this video, from which the still image above is taken.

The stem cells used in this study started out as a type of human skin cell called a fibroblast. These cells were genetically reprogrammed (as induced pluripotent cells – iPSC) to become human spinal neural precursor cells. The Parr Lab notes that the new cells are regionally specific (at home in a spinal cord), “anatomically similar to the host spinal cord.”

The cells that make up the “ink” are prepared in a media of growth factors and matrigel, a laminin-rich liquid that becomes solid at body temperature.

The printing of cell-laden inks as shown in the video linked above (College of Science & Engineering, UMN).

Loaded to the scaffolds, the cells were allowed to grow for 40 days, organizing as organoids and characterized by neurons, axons and nerve support cells. Paired scaffolds were then assembled with the channels towards each other, forming implants. Just after spinal cord transection, the implants were then placed into the 2 mm gap of the rats’ spinal cords.

So, how did it work? The Parr lab describes changes in a motor function score called BBB, a metric devised by researchers Michele Basso, Michael Beattie and Jacqueline Bresnahan. A score of 0 - 7 indicates isolated joint movements with little or no hindlimb movement; 8 - 13 indicates uncoordinated stepping; 14 - 21 indicates forelimb and hindlimb coordination:

At the end of 12 weeks post-transplantation, the 3D-printed organoid scaffold group exhibited significant functional recovery (8.4 ± 0.93), compared to the groups with scaffolds only (3.6 ± 1.25) and injury only (2.25± 0.72). The difference between the injury-only and scaffold-only groups was not significant. These results showed that the organoid scaffolds improved the functional recovery of the rats after SCI.

The illustration below, from the paper, shows both the cell and scaffold processes.

Figure 1. Han, G., Lavoie, N. S., Patil, N., Korenfeld, O. G., Kim, H., Esguerra, M., Joung, D., McAlpine, M. C., & Parr, A. M. (2025). 3D-Printed Scaffolds Promote Enhanced Spinal Organoid Formation for Use in Spinal Cord Injury. Advanced healthcare materials, 14(24), e04817. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202404817

Dr. Parr, who is a professor of neurosurgery at the University of Minnesota, provides some context on what those scores mean in her study:

A mean BBB score of 2.25 indicates rats typically have little or no movement of their hindlimbs. This reflects a very limited degree of recovery. Whereas a mean score of 8.4 shows uncoordinated stepping movements. These scores represent a progression from severe paralysis toward the ability to take some independent steps, indicating a partial, but not complete, motor recovery.

So, the rats weren’t walking well, but they were walking. The paper also reports significant improvement in motor evoked potentials at 12 weeks post-transplantation, measured using magnetic brain stimulation and electrodes in the lower leg:

These findings suggest that the organoid scaffolds enhanced neural connectivity and functional recovery across the transection site, enabling improved transmission of motor signals from the brain through the spinal cord to the muscles.

Acute Injury, Transection Model: Proof of Concept, not Clinical

As we know, a lot of SCI studies report recovery in rats that don’t ultimately translate to humans. It's fair to ask if this UM study is any different. There are many things still to work out before spinal cord organoid therapy is a thing. How would it work in a chronic injury, and how would that be surgically possible?

Given that a full or even partial transection is fairly uncommon in human SCI, how might Parr’s scaffold-cell idea apply to a more clinically common contusion model which lies within intact spinal cord membranes? This sets up a big issue in human SCI repair – placement of the scaffold/graft. Soon after injury the damaged area typically is encased by a type of scar. In the InVivo trial, they opened the membranes to expose the damaged area and physically removed the scar, not a trivial bit of surgery. Almost certainly an open cord will be necessary with the 3-D scaffolds, and that sort of detail remains to be worked out.

Parr notes that other studies using 3D-printed scaffolds loaded with neural cells have shown higher BBB scores than her team obtained. She suggests this is likely related to the different injury models. Her study used a transection injury wherein the spinal cord was completely severed. Other studies have used a hemisection injury (partially severed), leaving some spinal cord tissue intact. This might allow for nerve fiber sprouting and increase the chance of greater spontaneous recovery.

I asked Dr. Parr to speculate on next steps towards a translatable therapy for human spinal cord injuries:

We plan to combine both ventral and dorsal progenitor cells in the future [ventral for motor function, as used in this study, and dorsal for sensory recovery]. Using 3D bioprinting to spatially arrange vsNPCs and dsNPCs into assembloids that replicate features of spinal cord architecture. These “mini-spinal cords” show robust survival, patterning, and functional activity.

Scaling organoids and tissue engineering scaffolds to human size face significant biological and engineering challenges, with a primary hurdle being the inability to replicate the vascular and microenvironmental complexity. However, advances in bioreactors, bioprinting, and vascularization techniques are providing new strategies to overcome these limitations.

Parr thinks 3-D printing may allow patient-specific therapies:

The advantage of this technique is the ability to bioprint live cells directly during scaffold fabrication, allowing for precision placement of clusters of different cell types within designed scaffold channels. 3D printing will eventually enable us to design personalized neural organoid scaffolds for individual patients, to custom print any required scaffold shape with precisely positioned cells.

Continued research with improved designs like smart biomaterials that are stimuli responsive and shape memory materials can introduce a lot of possibilities in neuroregeneration and neuromodulation therapies.

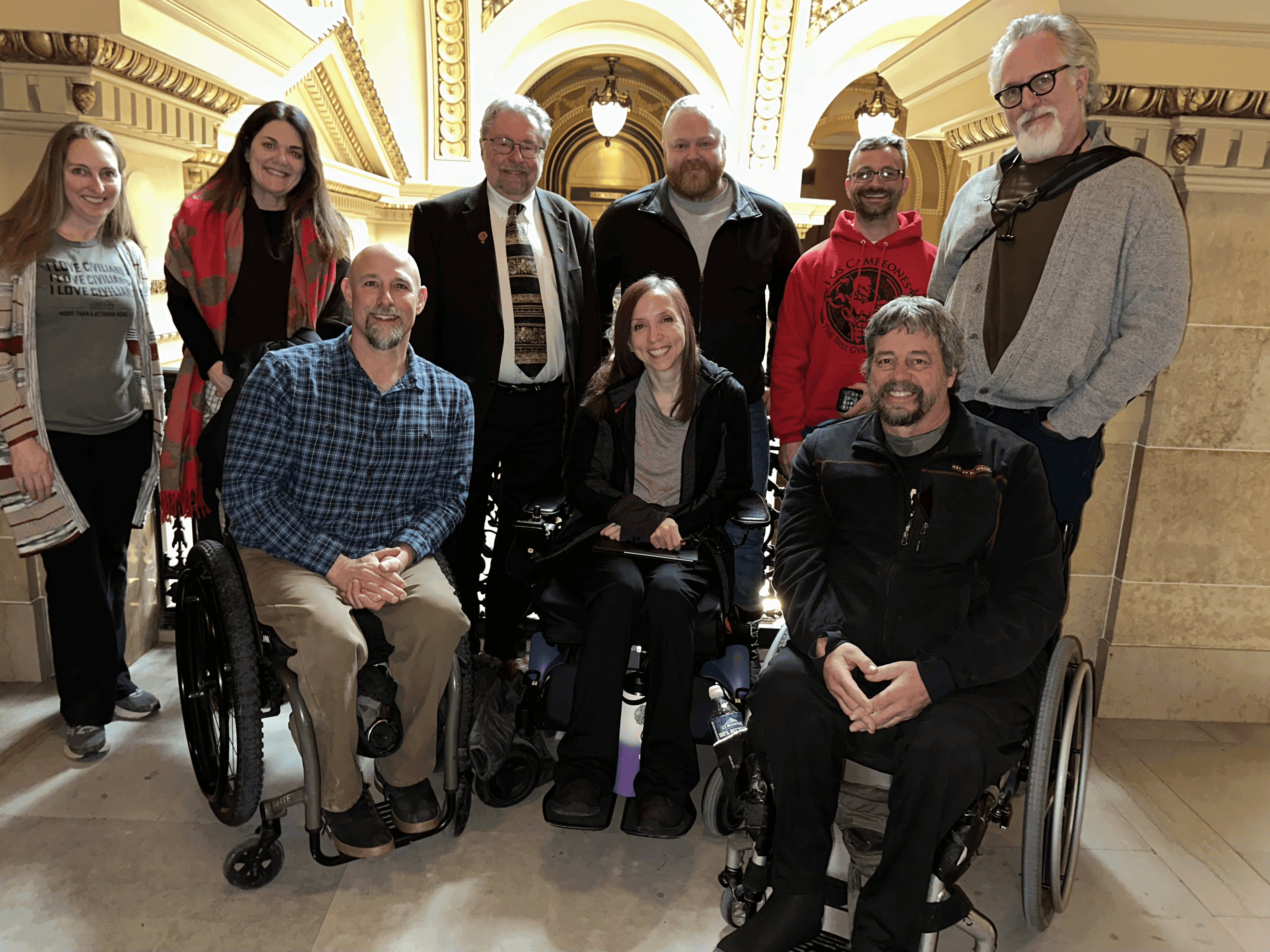

It's important to mention that this research was funded by the Minnesota State SCI/TBI Research Grant program, which was spearheaded by U2FP’s Matthew Rodreick and SCI advocates in Minnesota. This was the first of four state legislative bills U2FP has helped pass since 2018 that have to date garnered over $41M in SCI research funding.

If cell therapy evolves as a meaningful treatment option for SCI, as we’ve been anticipating for 20 years, the choice of cell will be a key factor, as will the use of guidance structures and scaffolds. We will continue to report on this exciting area of research.

Stay curious.