I was on a Zoom call last week with four Unite 2 Fight Paralysis colleagues, several members of the Ohio Cure Advocacy Network (CAN), and with two Ohio State scientists, Phillip Popovich and Dana McTigue. The reason for the call was to mingle science and advocacy by discussing a new study from the Popovich lab that was made possible by CAN-channeled money from the Ohio legislature.

This was the third time the advocates had met with an Ohio-based research team to assess the progress of their funding efforts.

So, let’s have a look at this potentially very cool approach to treat SCI, and also shine a light on an innovative advocacy effort via the CAN.

Old Drug, New Target

The Popovich study is titled “Acute post-injury blockade of α2δ-1 calcium channel subunits prevents pathological autonomic plasticity after spinal cord injury.” I invite you to read the published paper to learn a lot about the fascinating molecular biology; it represents seven years of work from the Popovich lab. In more general terms, the study is about repurposing a common pain drug, gabapentin, to protect people with new spinal cord injuries from conditions secondary to paralysis, including pain, immune suppression and autonomic dysfunction, e.g., blood pressure irregularities.

Popovich, who is familiar to the U2FP community both as a presenter at Working to Walk and as the director for our Science Advisory Board, explained the study and its clinical potential. McTigue, who is married to Popovich and who shares a similar research approach, filled in detail. (Watch their presentations and Q&A session from Working 2 Walk 2019 here).

Said Popovich, “It's a new way of using the drug in a way that could significantly change how people are treated and how they respond to their spinal cord injuries.”

SCI ignites a vigorous but unhealthy response in the damaged nervous system. Below the lesion nerve fibers sprout and form new connections. What happens, though, is that the sprouts make random, inappropriate connections, leading to pain, immune dampening and blood pressure management issues (the hallmark of autonomic dysreflexia -- AD). That’s what they mean by pathological plasticity.

But if the drug gabapentin (GBP) is introduced to the nervous system early enough (the experiments are done with mice, one day post injury) sprouting nerves can’t form connections (synapses, or as Popovich described them, “chemical handshakes”) with other nerves, thus the bad wiring cannot occur. This is from the published paper:

GBP-dependent inhibition of structural plasticity is associated with reduced frequency of spontaneous AD, reduced severity of induced AD, and protection from immune suppression. These therapeutic benefits persist for up to one month after stopping GBP treatment.

Gabapentin is FDA approved and super common, one of the top dozen most prescribed drugs in the U.S. It is mainly used as an anti-epileptic, anticonvulsant that affects nervous system chemistry involved in seizures. Marketed as Gralise, Horizant or Neurontin, it is also a first-line treatment for some types of neuropathic (e.g., SCI) pain. The new Popovich study shows that in his animal model, gabapentin is an effective prophylactic to prevent maladaptive neuron growth after high level SCI.

“Keeping those neurons from causing those harmful changes can keep people alive, keep them out of the hospital, and give them a much greater quality of life,” said Popovich.

“This is the first time a treatment has been shown to prevent the development of autonomic dysfunction, rather than manage the symptoms caused by autonomic dysfunction.”

The molecular biology of gabapentin in a damaged spinal cord is quite fascinating and of course, quite complicated. The drug binds to a specific protein (alpha2delta2) in the nervous system, thus slowing chemical processes related to nerve communication that are in turn related to pain, autonomic balance or immune function.

Popovich said he’d like to see gabapentin go from mice to humans, since it’s already approved and widely used. That may be possible if they can work out timing and side effects, and if they can convince doctors taking care of spinal cord injuries to use it.

“We don’t know how long treatment can be delayed after injury and still maintain the beneficial effects. Ongoing studies here in the Belford Center are optimizing this treatment onset window. We also don’t know if gabapentin targets other cells/organs in the body, so we’ll investigate the effects of this therapy on other tissues beyond the spinal cord,” Popovich said. He acknowledged that there could be effects on bone or liver function.

What is the best timing to apply, and for how long? Optimal dosage in a mouse won’t necessarily be the equivalent in humans. Getting the drug in the system before the aberrant circuits form should happen within days of injury, maybe a few weeks, but probably not a few months.

The mice got gabapentin for four weeks. Would two have worked? Poppovich said they’re working on all the dosage issues now.

What about chronic SCI? It’s not what this study is about but it’s not out of the question. Popovich postulated that if a chronic treatment somehow aggravated the spinal cord environment – something like a cell therapy or scar ablation – gabapentin might be useful to limit formation of bad circuits. In the case of spinal cord stimulation, which has been shown to awaken the spinal cord to a new wave of plasticity, likewise it might be possible to use GBP to fine-tune nerve growth and avoid unwanted results.

As an aside, Popovich told our Zoom group that he had corresponded with University of British Columbia scientist Kip Kramer, who reported that people who began treatment with gabapentin early after their injuries had much better motor recovery than those that didn’t. Why would this be? Apparently, GBP causes structural changes in the spinal cord – maybe by limiting needless and harmful sprouting – which may encourage appropriate axon growth. Kramer calls this “pharmaceutical pleiotropy,” getting two effects from one drug.

CAN Did It

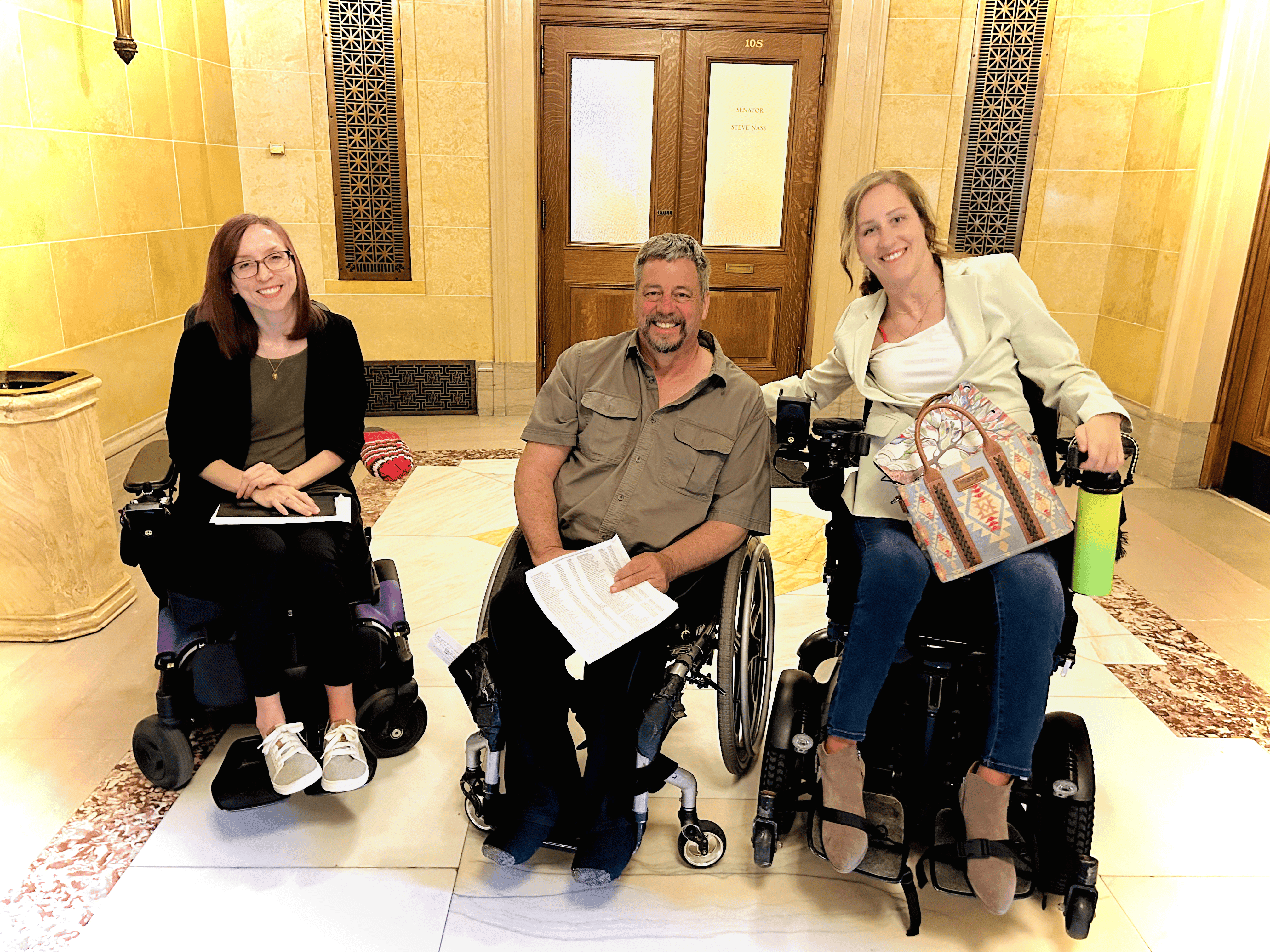

The Cure Advocacy Network helped get the Popovich study done. This U2FP initiative helps community activists organize and then persuade their state government to fund SCI research. The program started in Minnesota, expanded to Pennsylvania, Ohio and Washington. Wisconsin is getting closer, slowly, and Colorado and Texas are just getting lined up. In just a few years CAN advocates are responsible for adding $12 million to the SCI research pool in the U.S.

Here’s Ohio CAN advocate Peter Nowell describing how they got $3 million from the state for SCI research:

When we lobbied the Ohio legislature for support to get more state funding for SCI research, our group based in Toledo (I’m in Columbus) invited their then-Senator Randy Gardner to one of their meetings to meet real people with spinal cord injuries. Apparently, he was so moved by the experience he committed to doing what he could to support our efforts. We had considerable bi-partisan support for our efforts but having Senator Gardner as our champion really moved things along.

Gardner, meanwhile, was appointed Chancellor of Higher Education, and kept his commitment to the program. He found a way to fund the Ohio SCI initiative from his own budget by way of a state jobs program called Third Frontier.

Once the funds were secured, the Ohio community solicited SCI-related grant proposals from Ohio scientists. Those were scored by a review board, half of whom are members of the Ohio SCI community. So far, Ohio has funded six SCI projects, a mix, says Nowell, of preventative, curative and adaptive devices, ranging from primary research to “close to commercialization.”

Here’s Jake Beckstrom, U2FP CAN Manager, on the win-win:

The Ohio CAN advocates have now been on three Zoom calls with Ohio SCI researchers to discuss their projects. It is clear on each call that the researchers are excited to share their years of work, and I am pleased to see how hungry they are for feedback from the SCI community. With the advocates’ insight, researchers are able to tweak the direction of their projects to stay focused on the issues most important to the SCI community. For our CAN members, having close connections with multiple researchers and projects gives them a unique perspective on the research landscape in the state, better equipping them to press for financial support during future legislative sessions.

Jason Stoffer, CAN co-director, echoes Jake’s view that community input is a key element of the program:

The perspective of the “lived experience consumer” is invaluable. Without it, research continues in an echo chamber of assumptions. The CAN legislative funding model ensures that the SCI community voice is loud and clear in the projects that are funded.

You can find out more about U2FP's Cure Advocacy Network here.