This is the second in a series of articles with background and context for the 2021 Unite 2 Fight Paralysis Annual Science and Advocacy Symposium. This two-day event tells you what you need to know about the science to repair the injured spinal cord.

Mark the date: this year’s Symposium is October 22 and 23 in Salt Lake City, Utah. You can view the current agenda here, our speaker lineup here, and hotel info here. Then go register online here.

A quick reminder, the Symposium is not a “sit back and think about it” lecture series. It’s an interactive platform to seek common ground among the various stakeholders in the spinal cord injury community — those living with the injury, scientists, clinicians, funding agencies, biotech people, etc.

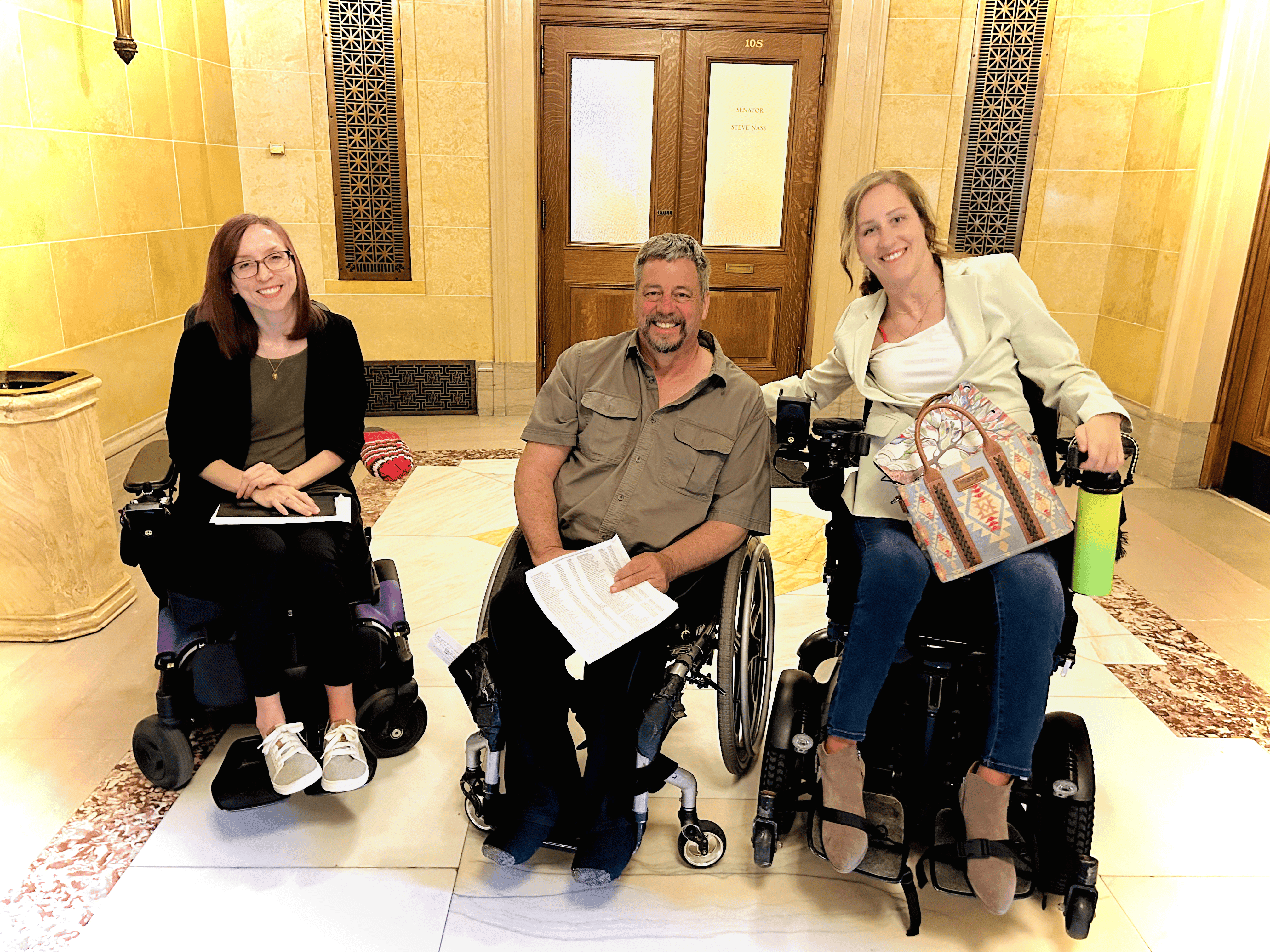

(In the header image, above, David Powers talks about his experience with an implanted device during our FES/Stim Participant Panel at our 2019 Symposium in Cleveland.)

So please, share your story and your priorities and engage with the many experts in the room during the sessions, during breaks or after hours in the hotel lounge. Scientists love to talk about their work, and getting to know the SCI community keeps their motivation sharp.

Replace, Regenerate, Rejuvenate.

Last week we spoke in very broad terms of research approaches to promote recovery in chronic spinal cord injury: Replace (add cells), Regenerate (grow nerve axons) and Rejuvenate (activating dormant nerve networks). We looked more closely at how the replacement strategy might work, from the perspective of the three Symposium presenters (Andrew Pelling, Michael Lane & Jacob Koffler) who will discuss their studies to repair spinal cord function by adding new cells. If you missed it, go here.

Let’s look at rejuvenation, which you might think of as the rousing of nerve cells that are still alive and home where they should be, but maybe asleep, and not functioning in harmony with spinal cord nerve circuitry. In the simplest terms, how might these cells be brought back online?

One answer opens the discussion to spinal cord stimulation, based on the idea that spinal cord nerve cells can be independently smart and active, despite missing their connection to the brain. The cells have a kind of automatic programming (called a pattern generator) for messaging motor/muscle cells; this can be switched on to some degree with intensive physical therapy, but much more so by application of pulses of electrical energy.

The stim reaches the dormant spinal cord by way of an implanted device or via skin surface electrodes. The concept has been validated in human trials, both implanted and transcutaneous — some people gain meaningful voluntary function that often remains after the stim device is off. Apparently, stimulation is more than a jolt of electricity, it encourages what scientists call plasticity — the cord circuitry remodels itself permanently.

The stim idea has had 10 years of traction, enough so now to promote commercial aspirations, high expectations, and even some early clinical applications.

Stim, Stimming, Stimmed.

Spinal cord stim is well represented at the 2021 Symposium, with the materfamilias of the concept, Susan Harkema, in attendance. She was lead author on the 2011 study that started the stim era, “Effect of epidural stimulation of the lumbosacral spinal cord on voluntary movement, standing, and assisted stepping after motor complete paraplegia: a case study.”

Harkema has a big program now at the University of Louisville and lots of projects with animals and humans. For example, she recently reported clinical trial results focusing on bladder function — combining activity-based recovery training with epidural (implanted) stimulation, resulting in improvements in overall bladder storage capacities.

The Kentucky Spinal Cord Injury Research Center, which houses Harkema’s lab, recently got a $7.8 million NIH grant to work with the big device company Medtronic to develop better implantable arrays to optimize spinal cord recovery. The ones they use now are designed and approved to treat back pain.

Harkema is joined at the Symposium by the company Onward, in the persons of co-founders Grégoire Courtine and Jocelyne Bloch from Lausanne University in Switzerland, and Dave Marver, CEO. They will explain their multi-center clinical trial for noninvasive spinal cord stimulation, and the pathway to getting stim on the market and in a clinic near you. Ed note: Onward is a major sponsor for the 2021 Symposium.

Onward’s current trial, UP-Lift, is testing skin surface stim to see if it improves movement and strength in the hands and upper limbs of people with incomplete cervical spinal cord injury (C2-C8).

Backstory digression: Harkema began her work with spinal cord stim at UCLA under the tutelage of Reggie Edgerton, who’s not coming but his shadow might show up. Courtine also trained in LA with Edgerton. Edgerton and Harkema, and others, formed a company a few years ago to make stim devices for SCI; that company was eventually merged with what is now Onward.

Going Clinical

Neurosurgeon/scientist Uzma Samadani represents the avant-garde of clinical spinal cord stim. She’s worked experimentally with colleagues at the University of Minnesota (including neurosurgeon David Darrow; check out his very cool U2FP CureCast interview) on a trial called ESTAND. They continue implanting epidural stimulators in people with SCI. It’s surgically similar to what they do in Louisville, but without the months of heavy-duty physical therapy before and after surgery.

Samadani is now taking things a step further — she is putting stim devices in her SCI patients, and having success getting them reimbursed by insurance companies. Here’s what she says about her talk:

There have been more than 50 patients implanted with these stimulators as part of clinical trials to improve quality of life after spinal cord injury. The surgery itself can be done as an outpatient and takes about two hours. Some of the patients who have had a stimulator implanted have recovered sufficiently to walk with a walker or exoskeleton, ride an assistive cycle, recover some bowel or bladder function and regulate their own blood pressure.

This talk will discuss the placement of devices outside of the research sphere. It will talk about the challenges spinal cord injured people have faced with regards to insurance coverage, surgical complications such as infection, difficulties with programming and failure to demonstrate improvement with the device. We will also discuss strategies for overcoming these difficulties so that more spinal cord injured people can benefit from epidural stimulation.

Note: Dr. Samadani is also founder of the start-up Oculogica Inc, which developed a concussion diagnostic tool called Eye-Box cleared for marketing approval by the FDA.

Keith Tansey will round out the discussion of spinal cord stimulation. He is an M.D. Ph.D., a senior scientist in the NeuroRobotics Lab at the Center for Neuroscience and Neurological Recovery in Jackson, Miss. He is professor of Neurosurgery and Neurobiology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, and treats patients at the Jackson VA Medical Center. Tansey also serves as a member of U2FP's Scientific Advisory Board.

Tansey plans to speak about how people are actually responding to spinal cord stimulation. Here is how he frames it:

I'll present our work on the spectrum of patient responses to spinal stimulation. We get to hear a lot about electrode placement but not so much on frequency and intensity of stimulation. We certainly hear VERY little about the heterogeneity of SCI patients. It's like the assumption is that one size will fit all, which never happens in medicine, certainly not in SCI. I'm sort of the guy who says proof of principle does not transform instantly into the standard of care.

Next time, more detail on the regeneration strategies you’ll see at this year’s Symposium.