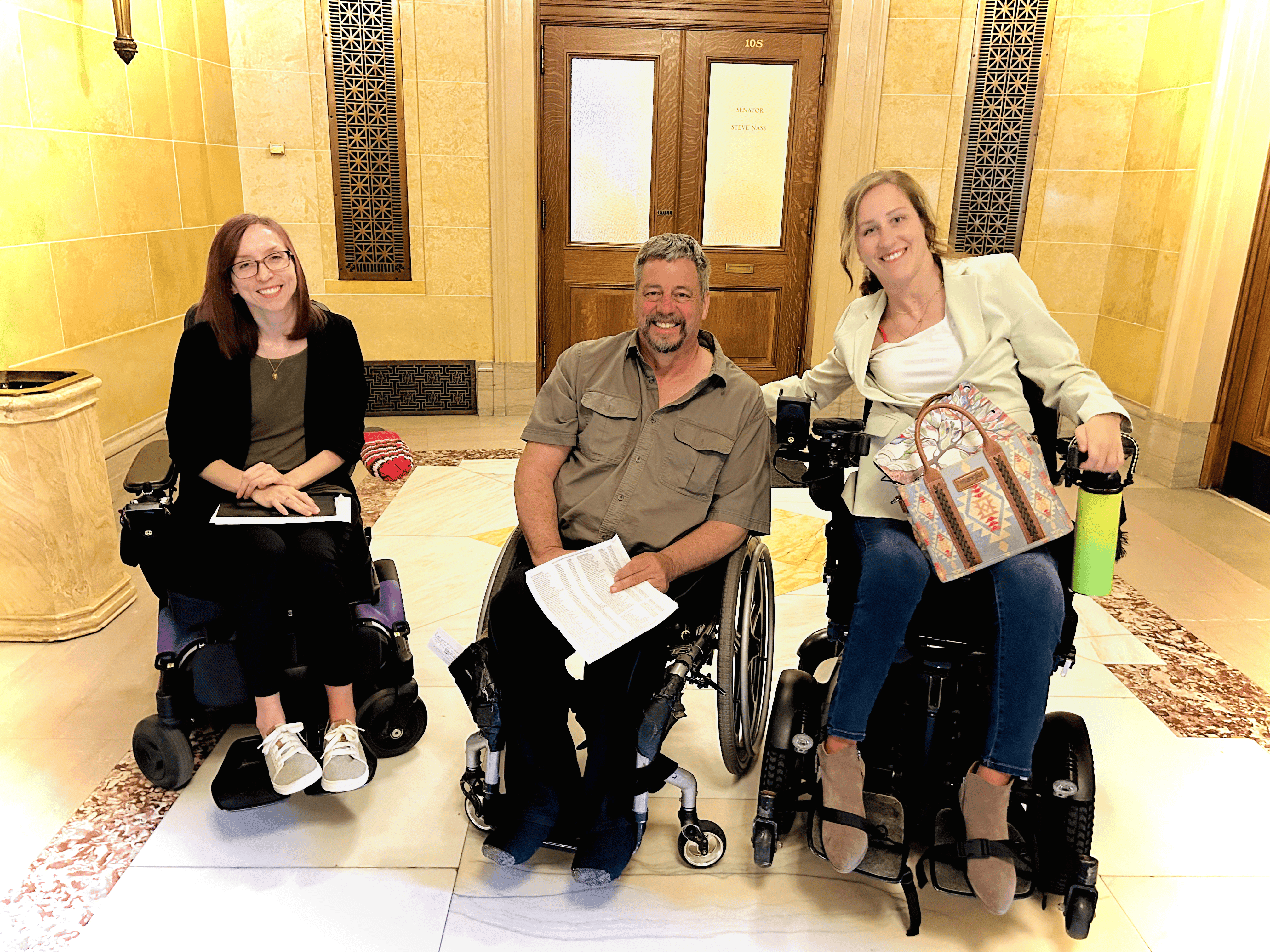

Unite 2 Fight Paralysis is very grateful to Aneuvo for sponsoring our 17th Annual Science and Advocacy Symposium, September 23 and 24 in Salt Lake City, Utah (register here). Aneuvo is a Los Angeles based company that is developing a neurostimulation device for treating spinal cord injury. They will begin a large, multicenter trial for its transcutaneous system within weeks.

Aneuvo is one of four companies currently working on transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation. All of these companies emerged from the Los Angeles neuromod culture at UCLA and Caltech, and the startup NeuroRecovery Technologies (NRT). Below is a brief synopsis of how we got to this moment.

In the Beginning

First, there was Reggie Edgerton. He’s a true graybeard in the field, the godfather of spinal cord stim; pretty much all work done today has a dotted line back to him. Edgerton is the founder of SpineX, an LA based stim company currently in the middle of a large clinical trial for its transcutaneous spinal cord stim device (more on SpineX’s evolution below). He’ll be presenting at this year’s symposium - don’t miss it.

Forty years ago, Edgerton helped revive an early 20th Century British hypothesis (based on cats with disconnected brains who could still move their legs) that the spinal cord was in itself smart, that with some sensory motivation the cord could initiate leg movements without brain circuitry.

To be sure, over many years, that’s been shown to be true: spinal cord stim has reanimated a lot of paralysis, in many animal experiments, and beginning in 2009, in the first human implanted with an epidural spinal cord stimulator. That operation took place in Louisville, KY and the research team included Edgerton, but it was led by his former UCLA post-doc, Susan Harkema, who is also participating in this year’s Symposium.

NRT started out making an implanted stimulation device to improve upon the off-the-shelf stimulators Harkema’s group employed. These electrode arrays restored function in paralyzed humans, but were FDA approved to address pain and were limited in how much they could be adjusted for SCI.

In 2011, physician/entrepreneur Nick Terrafranca shepherded a team, including Edgerton and investigators from Caltech and the University of Louisville; they formed NeuroRecovery Technologies with Terrafranca as CEO. The plan was to move the spinal cord stim concept from academia to industry. Raising money was never easy. The market is too small. Is this really needed? What's the ROI? If it’s such a hot idea, how come the big companies – Medtronic, Boston Scientific or Abbott – have not jumped in?

When NRT sought some extra tech help with electrode development (around 2013) they didn’t have to go far. Edgerton onboarded Wentai Liu, who had recently joined the UCLA faculty in the engineering school. Liu was already a neuromod luminary – he had invented a bionic eye implant that had been commercialized by a company called Second Sight.

In 2015, still hunting for breakout funding for the implantable system, NRT pivoted toward a noninvasive stim system. This was inadvertent. Terrafranca told the 2016 U2FP Symposium that Edgerton colleague Yury Gerasimenko went home to Russia for a while and showed up back at UCLA with a skin-surface stimulation concept. NRT locked down the intellectual property (IP), got some NIH grant money and began testing transcutaneous stim on human subjects. And it worked, not the same as the implanted units, but impressively: some subjects could stand, or make voluntary movements, or as Terrafranca told us, could “feel as though the core of their body was turned on.”

Onward

In 2019, after years of prospecting, NRT merged with a European neuromod company, GTX (formed by another of Edgerton’s former postdocs, Gregoire Courtine). GTX soon rebranded as Onward. The company, which has presented several times at our Symposium, including in 2021, now has what appears to be the inside track. They have the human resources in place and raised a decent amount of money to move both their transcutaneous and implanted stimulation platforms on a pathway toward regulatory approval and commercialization.

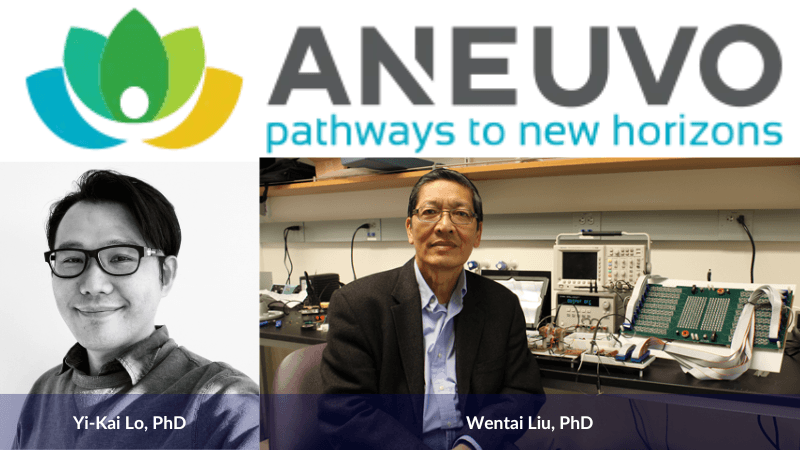

Meanwhile, Liu and his former postdoc, Yi-Kai Lo, started their own company, Niche Bio, in 2016. In 2021, they changed the name to Aneuvo and announced a transcutaneous stim device trial of their own. They call it ExaStim; the upcoming trial will enroll 150 patients at 10 sites, focusing on upper extremity function. (Lo described the Aneuvo strategy at the 2021 Symposium, which you can watch here at 2:15:10.)

Edgerton did not hop aboard the Onward bandwagon. Indeed, he and another NRT collaborator, Parag Gad, started a competing company, SpineX, to develop, test and market a transcutaneous device for spinal cord injury and other neurological conditions. They call their device SCONE; their current clinical trial is enrolling 130 patients at four centers, targeting bladder function.

Confusing? Wait, there’s even more. Gerasimenko, affiliated with the Kentucky Spinal Cord Injury Research Center/University of Louisville, and the Pavlov Institute in St. Petersburg, is scientific director for Cosyma, a company of Russian neurophysiologists making spinal cord stimulation devices, both implantable and transcutaneous.

The scorecard: NRT’s transcutaneous spinal cord stim device, in some advanced iteration, is part of the Onward portfolio. Three other companies, Aneuvo, SpineX, and Cosyma, all related to the original NRT development team, are testing their own units now.

Do we care?

This may seem like inside baseball medtech trivia, so does it matter? For investors, yes of course. For doctors, or potential users, probably not. Aside from wishing for some meta-analysis to clearly define the differences between all the spinal cord stimulation gadgets, maybe someone could please just tell us what works, what doesn’t, what type of patient is best suited for what type of stimulation, and what the expected outcomes might be.

It’s hard to resist seeing this as a race, but that’s the way das kapital works. What if all four stimulator systems work in unique ways, and all the companies make it to the marketplace? Good for them, everybody wins, cool for the people living with spinal cord injury. But in reality, the medical industrial system does not favor such happily ever after results. The company with the deepest resources and with the best protection for its intellectual property will have the clearest path to success.

More Stim on the Agenda

We should note that David Darrow, a Minneapolis neurosurgeon, is also on the 2022 Symposium program. He has been running an epidural stim clinical trial called E-Stand, getting similarly good results as the Louisville group, but without rigorous pre- and post-implant rehab. Darrow has his own company, StimSherpa, focused not on device development but on the optimization of any device to customize stimulation settings for each individual user.

Harkema continues to push the field of epidural stim. Indeed, she is hosting a three-day meeting this week called Moving Beyond Isolated Systems, featuring the world leaders in spinal cord neuromodulation, including Edgerton, Courtine and Darrow, as well as numerous prominent clinicians and researchers. U2FP will be there, and we will report on it.

Ethics check: What if the product outlasts the company?

Here's something to contemplate, based on the experience of Second Sight, the bionic eye company. Great engineering is meaningless if a company gets a product to market and can’t make the business model work. Read about what went on here.

In the case of Second Sight, 350 patients found out in 2019 that the company was facing financial headwinds and would not be able to support their implanted eye devices to the degree they were promised. For some, this was devastating news; they had come to rely on the eye implant for real life improvements.

Second Sight nearly went broke, to the point of auctioning off its lab gear, but found a merger partner earlier this year, Nano Precision Medical, a company that makes drug implants. No apparent synchronicity with bionic eyes, but perhaps a second chance for Second Sight. The company announced last week that the NIH has released $1.1 million of a $6.4 million, five-year grant to continue clinical trials for the eye implants. It isn't clear if this will also support and protect the people who already have an earlier version of the device.

Here's a cautionary take on Second Sight by technology ethicist Elizabeth M. Renieris of Notre Dame. She told the BBC:

This is a prime example of our increasing vulnerability in the face of high-tech, smart and connected devices which are proliferating in the healthcare and biomedical sectors.

These are not like off-the-shelf products or services that we can actually own or control. Instead, we are dependent on software upgrades, proprietary methods and parts, and the commercial drivers and success or failure of for-profit ventures.

Says Renieris, ethical considerations for medical technology should include autonomy, dignity, and accountability.

The scenario of product abandonment (or what about product failures, litigation and so on) makes you wonder if the big, permanent medtech companies might be the best home for neuromodulation. Medtronic has been supportive of the few dozen human epidural implants in the University of Louisville studies; Abbott has been very involved in the E-STAND trial. If either company decided to go all in on SCI neuromodulation? New ballgame.