This is not about a headline that got outsized media coverage, the usual MO here. It’s about one that got none. The story, “Abandoned: The Human Cost of Neurotechnology Failure,” was published last month by the top medical journal Nature. It throws uneasy shade across the implanted medical device industry – including companies that make bionic eyes and ears, and gadgets we talk a lot about, spinal cord stimulators for pain or functional recovery.

(Note: I touched on product abandonment briefly last summer within a longer piece on the history of spinal stim companies. In that piece, I mentioned an artificial-vision company that laid off most of its workforce, abandoning 350 or so people who were using its retinal implant.)

Medical devices offer life changing benefits for thousands of patients. What happens when companies go broke and no longer supply parts, software or tech support? Customers are high and dry, left to MacGyver tech on their own, or hope the bones of their device maker gets new life in a merger or reboot. They may also be left to wonder if their dead device will require expensive, risky uprooting.

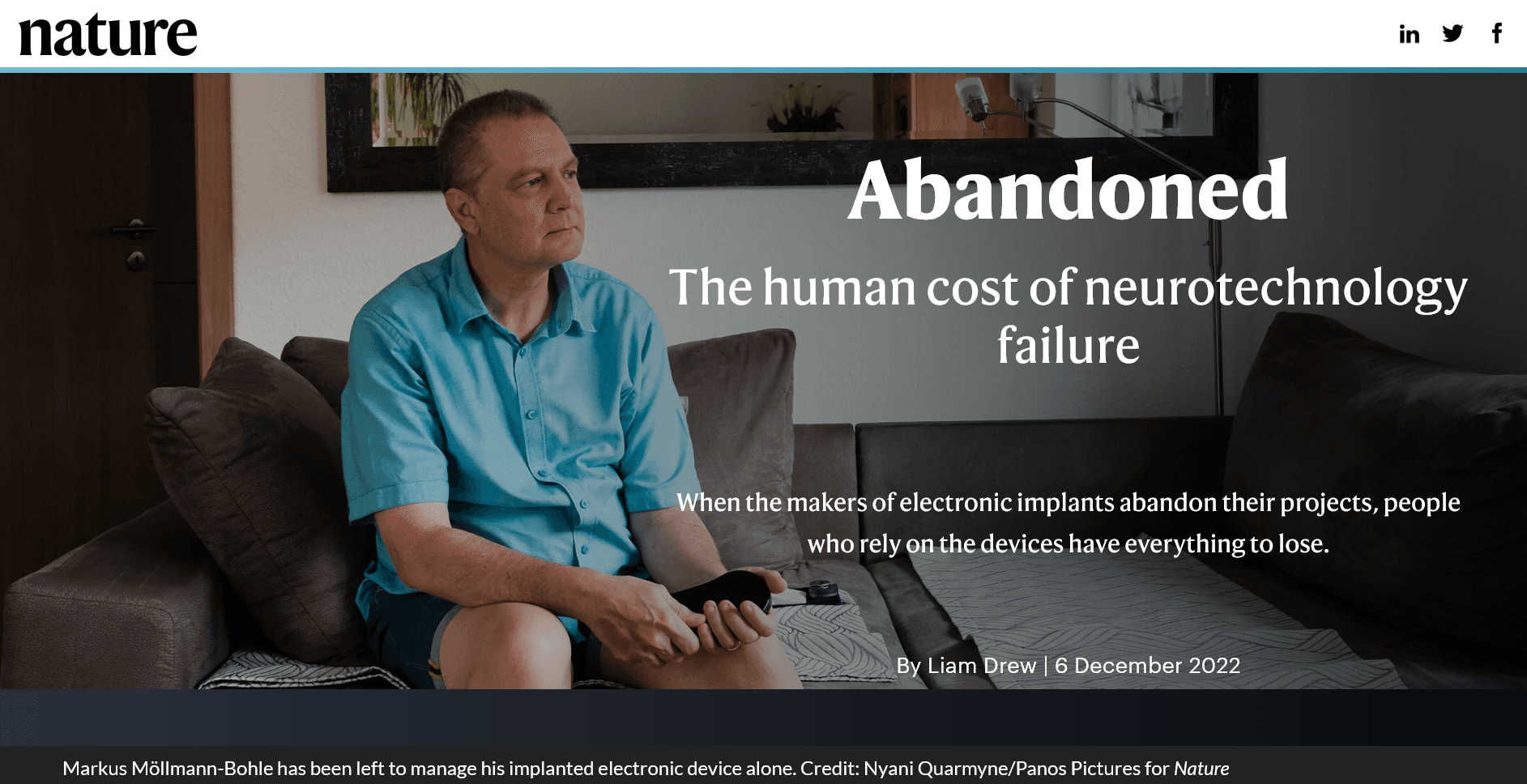

The Nature reporting by Liam Drew is broad and substantial; he uses text, images, video, and voice recordings to animate the story. I’m not going to recap the work. Read it yourself (it’s not written as obtuse science literature, it’s accessible journalism).

I do want to point out a couple of reported segments that directly converge with our spinal cord injury niche. Twenty-five years ago, the Cleveland company NeuroControl brought to market an FDA-approved functional electrical stimulation (FES) system called Freehand. The implanted device produced hand function when triggered by a shoulder shrug. Patients, about 350 in all, reported satisfaction. But when sales couldn’t meet company goals, the company went south.

Freehand is a sad story, but with a softer landing than some of the more desperate device abandonment cases Drew reports. The engineers at Case Western in Cleveland who designed the Freehand have committed to keeping the derelict systems running, scrounging up spare parts, and offering their continued services. Kudos to FES researchers Ron Triolo and Hunter Peckham for backing up NeuroControl, using funding from other ongoing clinical trials of FES systems.

Said Peckham:

“We understood that if there was something that they were benefiting from, if you took that away that would be another loss for them — when they had had such a devastating loss before.”

Jennifer French is one of Triolo’s ongoing FES trial participants. She was injured in 1999 and has become well known in the SCI realm as a co-founder of the North American Spinal Cord Injury Consortium and as executive director for the Neurotech Network, an advocacy group for neurotechnology. French has been using her 16-electrode FES system for more than 20 years – it allows her to stand, make pivot transfers, and pedal a stationary bike. But French understands first-hand her vulnerability. Her system, which never got commercialized, has failed four times. Case Western has always fixed or upgraded it. But what if the researchers are no longer interested in FES, or lose funding?

From Nature:

“I live every day with the fact that this technology might go away,” French says. But she takes heart in what she sees as the researchers’ unwavering commitment to her.

Triolo on ongoing trials, and commitment:

“… an individual who receives an implant [in a clinical trial] always has the option to be involved in one of these other studies and stay active. And that way we can maintain their systems for as long as we have research funding. It’s sort of like Tarzan finding another vine when he’s swinging through the jungle, you know? There’s always another study to be done.

“It gives us a framework and a structure that really allows us to fulfill what we feel is our obligation to these ‘test pilots’ who took a chance. We feel obligated and have a lifetime commitment to them as far as our ethics are concerned.”

Why does this abandonment discussion matter? Because a neuromod product may pop into your future – these devices are already being employed in spinal cord injury human trials, and treatments. It’s a huge industry that’s growing fast, globally, and the commercial track record has not been especially pretty. There will be more failures. “It’s impossible,” said Triolo, “for people not to know that this is becoming a bigger and bigger issue.”

We can expect the established, legacy device companies – Medtronic, Abbott, Boston Scientific – to keep a huge share of the business. We can expect them to be around long after implantation and we do expect them to provide service. Smaller, niche companies will also enter the market, including In the SCI world, where dozens of businesses are eyeing neuromodulation. What can we expect?

The Nature article wonders if industry will step up to assure that what they put in people will be maintained and managed. Will they build safety nets to ensure patient safety in the not so wild case management doesn't survive the market? There is zero expectation device makers will do anything about this issue on their own.

From Nature:

As money pours into the neurotechnology sector, implant recipients, physicians, biomedical engineers and medical ethicists are all calling for action to protect people with neural implants. “Unfortunately, with that kind of investment, come failures,” says Gabriel Lázaro-Muñoz, an ethicist specializing in neurotechnology at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts. “We need to figure out a way to minimize the harms that patients will endure because of these failures.”

OK, so what might companies actually do, or be forced to do?

From Nature:

… every device user, physician and engineer Nature interviewed thinks that people need to be better protected from the failure of device makers.

One proposal is that neurotechnology companies should ensure that there is money available to support the people using their devices in the event of the company’s closure. How this would best be achieved is uncertain. Suggestions include the company setting up a partner non-profit organization to manage funds to cover this eventuality; putting aside money in an escrow account; being obliged to take out an insurance policy that would support users; paying into a government-supported safety network; or ensuring the people using the devices are high-priority creditors during bankruptcy proceedings.

Triolo pitched the idea of market pressure, or perhaps branding: What if neuromod companies could capitalize on assuring that a product includes a patient safety net, even after company meltdown? Said Triolo: “If that is what it takes to have a competitive advantage, maybe that’ll be enlightening for our friends on the commercial side of things.”

Another way to protect people is by way of technical standardization. Electrodes, connectors, programmable circuits and batteries used in implanted neurotechnology are usually proprietary or otherwise difficult to source. Why not make them compatible across platforms?

A 2021 survey of surgeons who implant neurostimulators showed that 86 percent backed standardization of the connectors used by these devices. Richard North, president of the Institute of Neuromodulation, sees standardization coming.

“It’s inevitable that there will be standardization, and I think the companies involved recognize that too,” he says. … North thinks that standardization would boost innovation by encouraging companies to develop components that can be used with a wide range of existing systems.

Peckham hopes the neurotechnology field can go even further — he wants devices to be made “open source.”

Under the auspices of the Institute for Functional Restoration, a non-profit organization that he and his colleagues at Case Western established in 2013, Peckham plans to make the design specifications and supporting documentation of new implantable technologies developed by his team freely available. “Then people can just cut and paste,” he says.

“It starts with a commitment to the patients, to the people who can benefit from this,” he says.

Via e-mail, I asked Dave Marver, CEO of the spinal cord injury neuromod company Onward, about corporate responsibility and long-term patient support. They don’t have an implanted product but are working on one. He wrote:

Onward is building a company with the resources and capabilities to make an enduring contribution to the SCI community. We recognize the responsibilities associated with commercializing implanted therapies.

What about standardization, or open source?

Standardization of hardware is something that can potentially happen in neuromodulation. It has occurred in other, more mature fields. As Onward achieves scale, it’s something we can explore with the other implanted device makers.

As for the question about open-sourced designs: In my view, that’s just not realistic. It costs tens of millions of dollars to develop and commercialize a single implanted device platform. Without the competitive protections offered by patents and other forms of intellectual property, it would be impossible to raise the capital required to invest in new therapies and approaches. This is particularly important in a relatively small field such as SCI where it has been historically difficult to raise investment capital even with traditional IP protections.

So where does this leave things? Consumers do not choose their device company when they go in for some neuromod treatment. Should they? Probably not going to come to that. Doctors make the call. But what influences their decision? Device features and best interest of the patient make the list, but don’t forget corporate incentives, too. According to Stat News, doctors are well compensated to choose certain devices:

The medical device industry gave doctors consulting fees, lunches, lodging, and other incentive payments worth $904 million between 2014 and 2017, per a new study — more than $80 million more than the pharmaceutical industry lavished on physicians over the same time period.

Other than having a company’s gadget inside their body, or maybe a software upgrade, patients don’t have an actual relationship with the manufacturer. But there is an implied relationship, a trust, that is at the heart of this discussion of ethics.

As one of the target markets for neurotech, the SCI community needs to be aware of potential device abandonment, and must remain part of the conversation to address this.