August 28, 2025

Headline Patrol: 'World First'?

Sam Maddox

Today’s Headline Patrol considers a few recent SCI research news items, a couple of updates, one or two stories claiming to be revolutionary and several asserting “world’s first” status. We’ve got several prospective cell therapies, brain-computer tech, molecular nano scaffolds, and more, including an earnest measure of progress: clinical trials focusing on chronic injuries.

This just in:

World-first clinical trial commences to treat spinal cord injury.

This trial, using a cell therapy derived from nasal cells, is now recruiting patients. These olfactory cells have been shown over the years to promote nerve repair. Trial details here. U2FP has covered this story in a previous Headline Patrol (here) and on the CureCast podcast (here) with principal investigator James St John.

Image from the Griffith University website.

We like this because it's addressing chronic SCI with an experimentally established cell therapy, and because the science team took very seriously the input and advice of the Australian SCI community in designing and implementing the trial. Tip o’ the cap to Perry Cross and his Spinal Research Foundation for raising money, organizing support and championing this trial.

Here’s St John, head of Griffith University Clem Jones Centre for Neurobiology and Stem Cell Research and Principal Researcher at the Institute for Biomedicine and Glycomics:

Once the cells have been removed from the patient’s nose, they are then used to create an innovative nerve bridge which is about the size of a very small worm. The nerve bridge is then implanted into the spine at the site of the injury, offering what we think is the best hope for treating spinal cord injury.

Griffith is quite enthusiastic about this being “a revolutionary new treatment,” one they claim is the first ever such trial in the world. Maybe.

This is not the first ever SCI clinical trial using an autologous cell therapy for chronic SCI. The 2019 CELLTOP trial by the Mayo Clinic comes to mind, which infused autologous adipose [fat] derived mesenchymal stem cells in several patients, one of whom superresponded with surprisingly robust recovery (reported here).

SCI cell treatments have been used in chronic patients in other trials, including two California stem cell trials going back 10 years. Those (Stem Cells, Inc. and Neuralstem) were safety trials, meaning that the primary goal of the study was making sure the cells are safe. The Aussies are also measuring functional recovery as a co-primary outcome, but so did Stem Cells, Inc.

OK, St John and his team can have “world’s first” for this trial, the olfactory part is unique. But maybe we can agree, the science Olympics scorecard is not the point.

Another “world’s first” just came in over the transom:

World's first spinal cord transplant to take place in Israel, could allow patients to walk again.

A research group in Israel is preparing to implant a human spinal cord cell matrix using patients’ own cells. Per the Tel Aviv University press release, this is a “medical breakthrough that could allow paralyzed patients to stand and walk again . . . and marks a historic milestone in regenerative medicine.”

Image from the Jerusalem Post website.

First ever? Could be, the approach is novel, using autologous cells in an engineered matrix in scar-cleared chronic SCI. Historic breakthrough? Remains to be seen. Allow patients to walk? Not supported.

Tal Dvir, head of the Sagol Center for Regenerative Biotechnology and the Nanotechnology Center at Tel Aviv University, is leading the effort. He is also the chief scientist at Matricelf, an Israeli biotech company commercializing the technology. Said Dvir:

The goal is to build a small piece of spinal cord that behaves like the real thing. We can remove the scar tissue, implant the engineered tissue in its place and eventually fuse the new piece with the existing cord above and below the injury. Think of it as inserting a conductor between two cut cable ends, restoring communication.

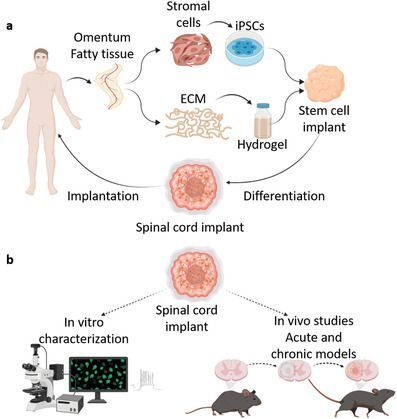

The procedure extracts blood cells from each patient then genetically reprograms them (as induced pluripotent stem cells directed to be spinal neurons). The iPSC cells are bathed in fat tissue (omentum) to create a custom 3D hydrogel scaffold. This engineered tissue is then implanted at the injury site, replacing scar areas that have been surgically cleared out.

Dvir and his team received preliminary approval from Israel’s Ministry of Health for a “compassionate use” trial in eight patients (this would allow Dvir’s group to treat patients ahead of full regulatory approvals).

Matricelf CEO Gil Hakim presented at the SCI Investor symposium in June. He did not offer a lot of scientific detail but described the overall business plan to rebuild the spinal cord, not address it symptomatically.

Checking the literature, there is a 2022 paper from this Israeli group, “Regenerating the Injured Spinal Cord at the Chronic Phase by Engineered iPSCs‐Derived 3D Neuronal Networks.” Per the paper, which used a mouse model and a transection injury:

In a novel approach to regenerate the injured spinal cord at the chronic stage, induced pluripotent stem cells are encapsulated in a hydrogel to potentially form patient‐specific implants. The cells are differentiated to SC motor neurons and form 3D neuronal networks that bridge over the injured axons. The implants reduce inflammation, enhance nerve regeneration, and significantly improve locomotion.

Figure 1 from Wertheim L, Edri R, Goldshmit Y, Kagan T, Noor N, Ruban A, Shapira A, Gat-Viks I, Assaf Y, Dvir T. Regenerating the Injured Spinal Cord at the Chronic Phase by Engineered iPSCs-Derived 3D Neuronal Networks. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2022 Apr;9(11):e2105694. doi: 10.1002/advs.202105694. Epub 2022 Feb 7. PMID: 35128819; PMCID: PMC9008789.

Also from the paper:

Mice were hemisected at T10, leaving the left hindlimb paralyzed. Six weeks later, the lesion site was re‐exposed, scar was removed, and a cell matrix was administered into the cavity. Mice were kept alive for an additional 8 weeks post‐treatment, during which MRI and behavioral studies were performed. The new cells seemed to integrate into the hosts and there were indications of reduced inflammation and gliosis at the injury site.

How significant was the recovery? The treated animals were better coordinated and had fewer missed steps of the injured foot in grid-walk analysis.

That is a long jump from the recovery of a moderately injured mouse to a paralyzed human patient walking again.

Meanwhile, there has been more animal work. On its website, Matricelf reports unpublished rat studies using a more relevant contusion injury model. Said the company, average BBB (locomotor) scores improved from 2.5 to 9.1 in the treated group, versus 5.8 in controls (note: it’s a 0-21 point scale), and 80 percent of treated rats “showed a significant improvement” compared to the control group.

Matricelf is currently running a study involving 166 rats across treatment and control groups, using iPSC-derived neural tissue from two donors. That’s not autologous and thus not the same as the customized personalized medicine they tout in the mission statement. But you can understand why – it’s quite time consuming and expensive to batch up animal-specific tissue implants. And thus we have arrived at perhaps the greatest challenge for the Matricelf strategy: scaling up the tissue product they call NewRal. How long does it take to batch up, what’s it going to cost, and can it get paid for?

According to an investor deck shared online, the prep is six months. The company estimates $1.5 million per treatment. Reimbursement? Details to come.

Here’s yet another world premier headline, this one from China:

“World's First -- XellSmart's Allogeneic iPSC-derived Regenerative Cell Therapy for Spinal Cord Injury Officially Approved by the U.S. FDA for a Registrational Phase I Clinical Trial.”

Can’t give this much space yet. So far it’s just a news story about engineered cells and a China clinical trial for off-the shelf iPSC-derived neural progenitors called XS228. There’s nothing I could find in the medical literature from the sponsor company or its founder to underpin any claims made.

Two related clinical trials are listed at ClinicalTrials.gov, one now recruiting for acute injuries, Safety and Early Efficacy of iPSC-Derived Motor Neuron Progenitor Cells (XS228) in Subacute Spinal Cord Injury: A Phase I Trial, the other not yet recruiting for efficacy only (primary outcome goal: changes in leg and arm function at 6 months).

The Phase II trial will soon be looking at about 60 participants, randomly assigned to get either XS228 or a placebo (inactive solution).

More breakthrough, more China, less validation

Brain-spine interface restores mobility in paralysed patient

Image from Surgery International website.

This came around last spring. It’s an interesting brain-computer-interface story, as related by a news article. Hard to know beyond this reporting as no follow up with the Chinese research team was available. The gist of it is that four paralyzed participants reportedly regained control of their legs within 24 hours of a minimally invasive brain-chip and spinal cord stim surgeries to create a “neural bypass.” By placing electrodes in the brain, using a computer plus some machine learning algorithms to decode them, and adding electrodes on the spinal cord to allow a bridge over the damaged area.

If this sounds familiar it is because this is the same approach the Gregoire Courtine group in Lausanne, Switzerland used in 2023 and which was the focus of a 60 Minutes segment earlier this year. Brain electrodes decode intent, which is directed to stimulation parameters in the spinal cord resulting in volitional movement.

According to reporting in the South China News, one patient (Lin, 34 years old, two years post injury) regained leg movement and walked five meters with support after two weeks. The Fudan University (Shanghai) website quoted Lin at a follow-up appointment: “My feet feel warm and sweaty, and there is a tingling sensation. When I stand, I feel the muscles in my legs contracting. I used to cry every day," Lin said. "Now, I can walk again.”

Here’s another headline regarding this Fudan BCI study, revealing a kind of hometeam jingo journalism: China’s neurotechnology breakthrough challenges Elon Musk’s verdict on paralysed patients. So, it is a fair question, how is this work in China different or better than the Musk startup’s Neuralink system?

Image from the South China Morning Post website.

We don’t know, except Neuralink isn’t reporting nerve plasticity. Here’s the South China Morning Post’s take:

While Musk's BCIs tether patients to computers, China's brain-spinal interface reignites dormant nerves, sparking what researchers call "neural remodelling" – a rewiring of the nervous system that could ultimately free patients from devices altogether.

This not only challenges America's dominance in neurotechnology - it also redefines the future of treatment for paralysis.

Meanwhile, Neuralink said they’re hoping to do 25 or 30 implants this year. The company announced in late July that they have approval from U.K. authorities including the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) for GB-PRIME, testing robot-implanted nerve chips in people with high cervical injuries, enabling control of devices with thoughts. (Check this story out if you want to see how the Neuralink device changed the life of the first participant, Noland Arbaugh.)

I wrote to the principal scientist of the Chinese BCI group, Jia Fumin, to get more information. I never heard back. Lost in translation, perhaps. But if this develops and shows up in the SCI literature, we will follow up.

Bride of Dances with Molecules

The headline says Regenerative spinal cord injury therapy repairs tissue and reverses paralysis; it should say “Supramolecular nanotech polymer gets approved as an Orphan Drug for SCI.” That FDA designation incentivizes drug or device development in rare diseases or conditions with tax credits for clinical trials, market exclusivities, etc.

Surgical procedure. Image by Pfree2014 - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

This is a familiar story here, as we’ve followed Samuel Stupp’s work for four years, had him appear at our annual Science and Advocacy meeting and featured him on the CureCast podcast (here). He assembles tiny molecular scale polymer nanostructures, loads them with nerve promoting drugs, and places them in the injury site after acute spinal cord trauma.

Stupp’s polymer is injected by syringe and forms itself into a tubular matrix – a miniature, biodegradable scaffold. In Stupp’s first SCI-related study, two biologics were attached — one for laminin, which promotes axon growth, and one for fibroblast growth factor 2, which promotes cell growth and survival. Once the regenerative cargo is offloaded, the polymer breaks down in the body with no known side effects.

Per Stupp in the 2021 paper, his polymer improved spinal cord injury recovery in five ways: regenerated axons; reduced scar barriers to nerve growth; rebuilt myelin (axon insulation needed for electrical efficiency); and formed new blood vessels, thus keeping more motor neurons alive.

Amphix Bio, a company spun out from Stupp’s Northwestern laboratory, is hoping to recruit participants in late 2026.

One last headline

This is a follow-up to recent reporting: Lineage Announces Dosing of First Patient in New Clinical Study of OPC1 for Subacute and Chronic Spinal Cord Injury.

These are the well known OPC1 embryonic cells used in the groundbreaking 2010 Geron trial, which became the Asterias trial, and now Lineage, covered in detail here. We’re happy to see them put to work in people with stable, chronic SCI.

So, there has been some progress – too slow but real – made on the translation front; movement is clear because several of the studies and trials mentioned above continue previously covered research news. There seems to be a lot of emphasis on being first to do a specific intervention, which may be important to state-supported research in Israel and China, and even Australia.

Being first matters to the investigators, and their investors. In the longer view, the real score is still zero. So we will continue to watch and share what matters most – which cells or tissue implants or nanostructures or drugs or devices actually work.